Arabian floating architecture in Sicily

I just finished Peter Robb’s quite brilliant ‘Midnight In Sicily’, and I can hardly say enough about the book. It’s easily as good as his subsequent ‘A Death In Brazil’, and both are careering straight to the upper reaches of my favourite books list. Numerous passages demand further attention, including about cities, culture and history, but I was struck by one that might be interesting to consider from an architectural angle.

The ‘mattanza’ was the ritualistic annual slaughter of tuna by Sicilian fisherman, as the giant fish entered the Mediterranean each spring to breed. As a genuine cultural practice, it’s all but extinct now and according to Robb, the south coast of Italy is dotted with abandoned tuna works.

As with much in the Mezzogiorno region of Southern Italy, it comes from the Arabs. (Much is made by Robb of Africa’s presence across the water from Sicily, with Tunis being closer than Rome, geographically and culturally.) And as with much else in the Mezzogiorno, the entire event is laden with symbolic meaning. It was a truly savage ritual, ending in a frenzy of blood and flesh — Robb doesn’t have to point out the obvious parallels with the numerous mafia slaughters described elsewhere in the book.

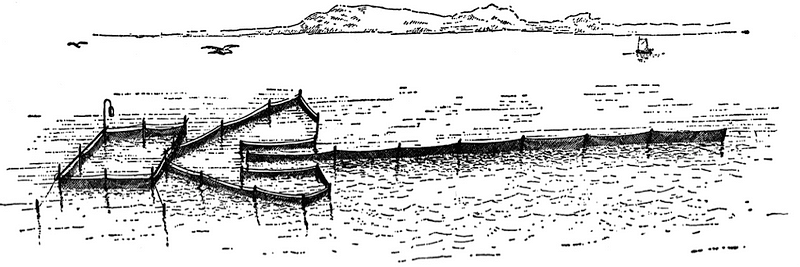

Aside from the cultural practice and Arabic roots, I found the carefully orchestrated architectural element of a mattanza interesting. The fisherman wait in boats, often spending days at sea in the blazing sun, having constructed an elaborate cage of nets called ‘la tonnara’. Tonnara seems to mean both tuna fishing station and the nets at the same time, as if the nets are the temporary architectural element, the transient threshold of a larger structure.

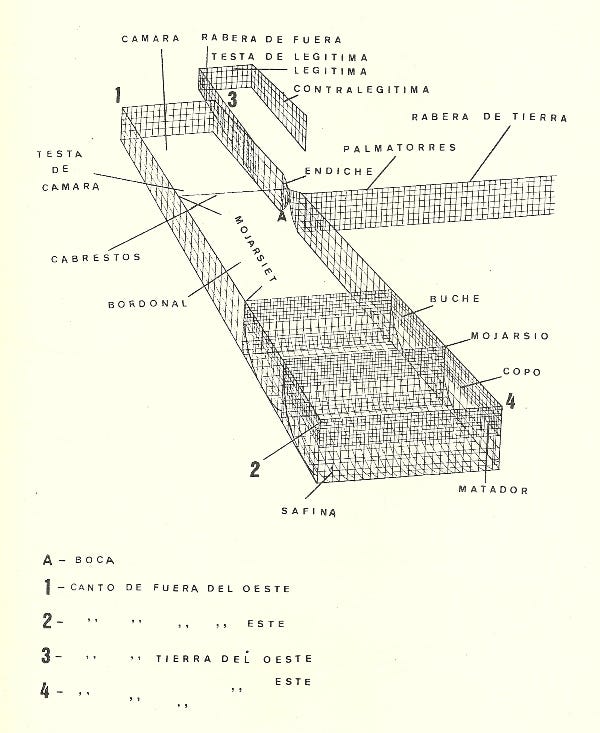

La Tonnara is a fluid, floating architecture, a sequence of nets, which form ever decreasing chambers, funnelling the huge schools of unwitting tuna towards a final netted cage, called ‘The Chamber of Death’. The ritual was captured in a passage written by the marquis of Villabianca almost exactly 250 years ago, on May 26 1757, in which he described the structure as:

The walls, the columns and the beams that form an atrium of nets under the sea and what would be a marvellous palatial house on land … This maritime house consists of four chambers. The first of these is called the Square Chamber, because of its square shape … Through its door, which is the main entrance to the tonnara, the tune enter, and they are happy to make their entry there, being unaware of this insidious art by which Man receives them in this ingenious edifice … This chamber leads into a second, which they call the Small Chamber … There follows the third chamber towards the east, whose entrance is called Clear, because it is made with a long mesh, and then the fourth and last and final one called the Chamber of Death … where the solemn festive sacrifice is made. … (There) the fishermen, who do all the killing in the livery of the owner of the tonnara, raise the nets of the said fatal chamber by means of pulleys to the surface of the water, then throw themselves like so many starving wolves on the fish that have been brought up and hurl sharp spears and harpoons at them and with these they massacre them and take their lives. [Marquis of Villabianca, 1757. Quoted in Peter Robb, ‘Midnight in Sicily’]

I like the idea of these nets as a form of building, hinted at through the naming of chambers, floating gently across the Mediterranean until it hits a school of tuna, or vice versa, and its gruesome purpose is realised. It then disappears, only to reappear next spring.

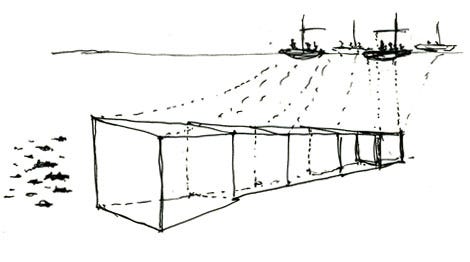

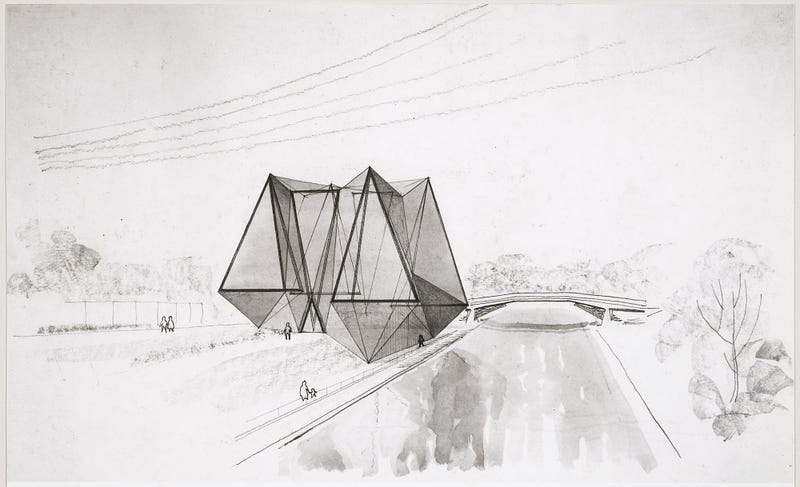

Reading Robb, I first imagined tonnara a bit like my sketch below:

But locating the drawings and photographs of tonnara below, I realise it’s a far more complex structure, with wide sweeping wings designed to capture the maximum number of tuna in that ‘Square Chamber’, inexorably guiding them towards the final chamber. As ever, I’d love to find more references and diagrams of these structures.

Perhaps the intricate interior and labyrinthine nature of the structure recalls its Islamic origins too. Elsewhere, Robb almost literally stumbles across the realisation that many of Sicily’s towns still retain the original Islamic urban planning, when trying to find a way out of Racalmuto:

I was struck by the interiority of Islamic design in cities and buildings. Unlike European architects who were much concerned with a building’s external appearance, Arab architects ignored or minimized the outside and turned wholly inwards to the harmonies of interior space and interior decoration. The same was true of Arab town plans, with their bewildering maze, for those that didn’t know them, of irregular streets, blind alleys, hidden almost private courtyards on to which a cluster of houses linked by family or trade would open. What I was starting to discover was how much Racalmuto, like many other old Sicilian town centres, kept to the patterns laid out by the Arab planners a thousand years ago, patterns that persisted through the monumental design imposed by later rules, even though the mosques and nearly all the Arab buildings themselves had long ago disappeared. [Robb]

Robb doesn’t make the connection in the book, but perhaps there are shared formal elements and sensibilities in the ultimate blind alley of la tonnara and the Arabic town plans which underpin the crumbling layers of the Mezzogiorno. The same maze of spaces, sometimes bewildering tuna, sometimes sheltering people. Is the interiority a simple function of the “pitiless” sun of the South, the impermanence of building materials, or a cultural artefact — or is it impossible to unravel even those threads?

It seems that Sicily itself is near-impossible to comprehend, and realising this, Robb tries to at least conjure the sense of it, through an impressionistic and heady stew of references, experiences and testimonies. We come back to layers of meaning in the names:

The memory of Sicily is in its names. The chief, the fisher foreman who chose the place and coordinated and ordered the mattanza of the tuna and swordfish, was always called in Sicily by his Arabic name. He was the rais, in Arabic the commander. The Palermo prosecutor Lo Forte described Riina’s prolonged massacre of his rivals as a mattanza. And the room in Palermo at piazza Sant’Erasmo where the mafia boss Filippo Marchese interrogated, tortured, strangled and dissolved his victims in acid was known as The Chamber of Death. [Robb]

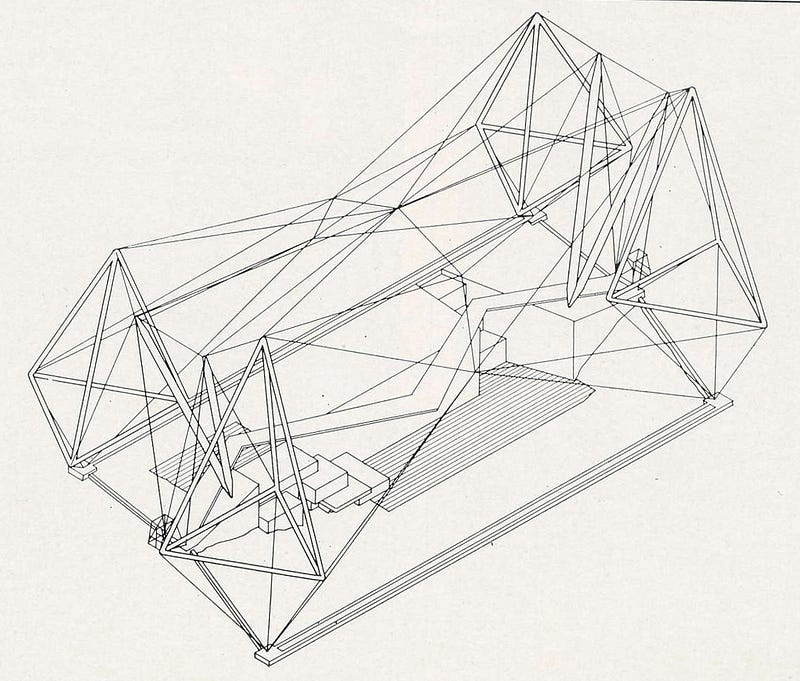

Aside: Returning to nets and structures, I also recalled land-borne, or airborne, netted architecture, in the slightly more benevolent form of Cedric Price’s aviary at London Zoo. I seem to remember that in Price’s original idea, the aviary was mobile, able to move under the collective command of the birds. A self-aware flock, flying in one direction, would strain at the nets along one edge of the structure, slowly dragging it through the zoo. Or did I make that up?

Of course, it is possible to build complex, labyrinthine interior-orientated structures without it leading inexorably to a chamber of death. Desirable, even. On Arabic urban planning, note for instance that Koolhaas and Foster have both been drawing from this deep well recently. But perhaps the most interesting thing I’ve read about the Western focus on the exterior, at the expense of the essentially more important interior, is in Juhani Pallasmaa’s supreme book ‘The Eyes of the Skin’. In this context, it’s not only interesting that Pallasmaa describes “the haptic city” as one of “interiority and nearness”, but that he illustrates this with a photo of the hill town of Casares, southern Spain, which is — of course — built to a Moorish plan.

For Robb in Racalmuto, the town plan constricts and entraps, though perhaps the surrounding context of Cosa Nostra and the unified Italy’s slow murder of the Mezzogiorno is as much to blame as the immediate warren of streets. Elsewhere, reading Robb suggests an affection for, and affinity with, the tightly bound streets and dark crevices of Naples and Palermo. In this, he is with Pallasmaa, for whom the chiaroscuro rendering and sinuous haptic presence of the traditional, pre-modern city plan provides a heightened sense of urban living and being, richly informed by memory, that can truly benefit the city and the citizen.

This piece originally published at cityofsound.com on 22 May 2007.

Leave a comment