Notes after a first trip to Australia in April 2006

Australia was familiar — same language; a shared culture to a large degree, more so than America — but utterly foreign at the same time, and I hadn’t expected that difference to be articulated so immediately through its natural environment. In response, here’s an impressionistic selection of notes and images on encountering Australian flora, fauna and environment for the first time, influenced partly by my simultaneous reading of Robert Hughes’s The Fatal Shore.

This approach — reading historical accounts, whilst encountering the contemporary — is lifted specifically from Jonathan Raban’s Passage to Juneau. I’ve also folded in other accounts of so-called New Worlds, including Brazil and America, drawing from art, film, food and books, all circling around the sense of environmental difference to Europe.

Note: Despite the title of this piece combining an earlier Hughes classic with the concept of the ‘New World’, amidst talk of flora and fauna, I’ll hold off the Georgian vocabulary. I’m aware of the politics of a white Englishman writing about such things. I’m not Australian. Of course, there are indigenous readings of this ‘world’ – actually the oldest continuous civilisation on Earth – that would be far more refined, interesting and appropriate. But, following Raban and Hughes, I wanted to match the confusion, mystery and awe I felt with that of other Western travelers, for all the complexity and privilege of that intent. My indigenous education would come later, and open my eyes rather more, to the appalling crimes and consequences of colonialism as much as the wonder of the environment. Further caveats: I saw, oh, less than 1% of Australia, and it’s all too easy to fall into cliché when confronted with the unexpected. Either way, here goes.

As soon as I stepped off the plane at Brisbane airport, my jetlag-frazzled senses seemed instantly reorientated towards the natural world suddenly around me; an indistinct sensorial collision involving me and a flurry of trees, shrubs, birds, insects, spiders, flowers, soil and so on. The intense sub-tropical heat and light almost over-exposed everything initially, heightening the effect as my squinting eyes slowly began feasting on everything around me …

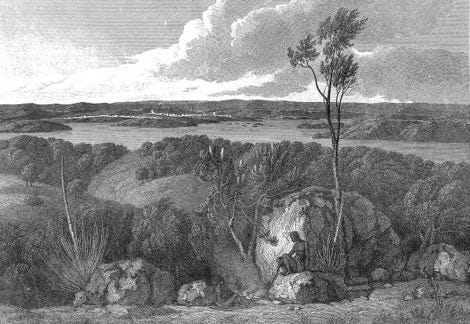

I have already posted one of the more optimistic observations from the English settlers, that of Arthur Bowes Smyth as he saw himself surrounded by an “enchantment”, sailing into Sydney harbour.

The finest terra’s, lawns and grottos, with distinct plantations of the tallest and most stately trees I ever saw in any nobleman’s ground in England, cannot excel in beauty those wh. Nature now presented to our view. The singing of various birds among the trees, and the flight of the numerous parraqets, lorraquets, cockatoos, and maccaws, made all around appear like an enchantment; the stupendous rocks from the summit of the hills and down to the very water’s edge hang’g over in a most awful way from above, and form’g the most commodious quays by the water, beggard all description.” [Arthur Bowes Smyth’s journal entry for January 26, 1788. Quoted in The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes]

Captain John Hunter, also on the First Fleet, saw the landscape in similarly hopeful terms:

Tolerable land … which may be cultivated without waiting for its being cleared of wood; for the trees stand very wide of one another, and have no underwood; in short, the woods … resemble a deer park, as much as if they had been intended for such a purpose. [From The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes]

The trees were actually spaced in this way due to careful firestick farming by indigenous people. And Port Jackson was as far from a deer park as it could be. After the initial bewilderment and amazement, however, most reactions turned as depressed as their first crops (as with the English settlers in Virginia, who were saved by the Algonquin). The attempt to treat this foreign soil as if it were an impossibly large Kentish vegetable patch was doomed to failure.

With the benefit of two subsequent centuries worth of traversing, studying and generally conquering every inch of the globe, such naïvety seems laughable. But how could settlers react to such entirely new terrain? It’s now a rarity, several hundred years into the colonial age. The responses to the direct impact of Australia, collated in the numerous First Fleet diarists such as Watkin Tench, John Hunter, Bowes Smyth etc, betray a bewilderment with the environment in particular.

“The comparison of the harbor landscape with an English park is one of the more common, if startling, descriptive resources of First Fleet diarists. Partly it came from their habit of resorting to familiar European stereotypes to del with the unfamiliar appearance of things Australian; thus it took at least two decades for colonial watercolourists to get the gum trees right, so that they did not look like English oaks or elms.” [From The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes]

It’s reminiscent of those artists, elsewhere on the planet at the time, trying to describe the modern industrial city — equally without historical precedent. The Shock City of Manchester became a stop on the European Grand Tour for a while, as amazed visitors had their sense assaulted by an urban form without precedent. There’s an inadvertently hilarious painting, in the softly dappled English landscape style of Constable, in which someone tries to depict Sheffield; an arcadian scene, broken only by a sudden dirty blotch of smokestacks in the middle distance. Similarly this painting of Manchester in 1852, in the same spirit.

British painting had not developed a suitable vocabulary for this, nor Australia.

Nor had the settlers in Australia developed a suitable horticulture.

“The unprepared new arrivals struggled with a version of nature that simply rejected the contrivances of their imported culture. The terrain suited hunter-gatherers, but lacked grasses that could be farmed. Hard-hoofed European animals did not thrive on the leached soil; when sheep and rabbits were introduced, their grazing reduced half the continent to a desert. The local fruit was not succulent, the timber was tougher than any axe raised against it and the narrow-leaved shrubbery, adapted to survive fire and drought, ripped the skin of explorers or escapees from the prison camp. The bedrock lacked the limestone that was necessary for cement and the red clay from which bricks could be made, so the colonists could not build houses..” [Peter Conrad’s review of Thomas Keneally’s The Commonwealth of Thieves in The Observer]

Hughes describes how the settlers had no useful skills anyway — “absurdly ill-chosen for the task” — another sign that the British saw Australia as no more than a dumping ground, not really a colony at all.

Peter Carey draws from Watkin Tench’s accounts of gnawing starvation almost killing off the first settlers, yet “while Tench fretted, the indigenous people ate possum and snake and feasted on bunya seeds and a huge variety of wild food which the invaders would not touch to save their very lives. They did not learn either. A century later the explorer Burke died of starvation in a landscape where healthy families of Aboriginals were going about their daily business.”

The scientists on Cook’s vessel were amazed at the “staggering quantity of ‘nondescript’ (unclassified) plant life. Eventually, the young botanists were to bring back 30,000 specimens from their voyage, representing some 3,000 species of which 1,600 were wholly new to science.” [Hughes] There are some quite beautiful botanical drawings from the Endeavour’s voyage at the National History Museum.

In early parts of the voyage (Sydney) Parkinson was able to keep up with the pace of discoveries, finishing his coloured sketches, but later, overwhelmed by new specimens, he could only sketch and partially colour-in significant portions of each plant portrait, just enough to give an overall scientifically significant view of the plant specimen before it wilted and lost its colour. [NHM]

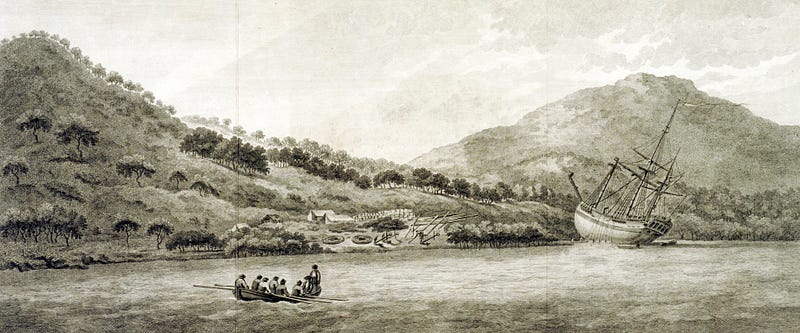

In The Fatal Shore, Hughes describes the moment, the afternoon of January 26th 1788, when a fleet of eleven vessels entered Port Jackson (now Sydney Harbour), gliding into the natural harbour intending to settle for the first time:

One may liken this moment to the breaking open of a capsule. Upon the harbour the ships were now entering, European history had left no mark at all. Until the swollen sails and curvetting bows of the British fleet came round South Head, there were no dates. The Aborigines and the fauna around them had possessed the landscape since time immemorial, and no other human eye had seen them. Now the protective glass of distance broke, in an instant, never to be restored … [From The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes]

A similar event is captured in the opening to Terence Malick’s film The New World, a flawed yet beautiful film about ‘the capsule breaking open’ on Virginia in 1607, punctured by an earlier British colony.

Malick, and to some extent cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, has such facility with light, sound, pace and yes, fauna and flora, that you forget the presence of Colin Farrell and an unavoidably banal love story and instead focus on those ‘swollen sails and curvetting bows’ slowly but surely gliding between the mangrove banks of a Virginian river, and share the sense of awe, wonder and fear of the aboriginal North American Algonquin people flickering through the trees.

As with Malick’s earlier Vietnam-based movie, The Thin Red Line, the soundtrack later drops out to the alien noise of cicadas, frogs and birds whilst the cameras glide and hover like dragonflies over deep green water shrouded in mangroves, or tumbling silvery over rocks.

Switching to the Algonquin view throughout the film, or attempting to at least, embodies a sense of wonder in nature. Malick also tries to conjure the sense of awe, wonder and fear for the English settlers. These are people randomly extracted from a late-medieval England; in 1607, we’re still largely pre-industrial revolution. It’s entirely surreal to see settlers dressed in full armour carrying halberds and pikes, struggling knee-deep in Virginian swamp, soaking with sweat in sub-tropical humidity. One places the colonial capture of America from its owners amidst modernity; you forget how early it started.

As noted, the narrative itself cannot escape concerns about mythology and sheer schmaltz, yet the overriding feeling throughout this gorgeously constructed film is one of genuine shock and awe at a new nature entirely foreign. Malick leaves us gazing in rapture at a New World which is impossibly beautiful and terrifying. Equally, no Englishman had ever heard nature provide a continuous aural backdrop, a wall of insect noise punctuated only by the calls of strange beasts and birds. The film would work perfectly well without any dialogue whatsoever …

Interestingly, one moment of dialogue is telling, in relation to Australia. Christopher Plummer’s character, assuming he is born to leadership and almost comfortable with it too, leads the rabble of settlers with a rousing if misplaced speech about a promised land, a New World full of bounteous riches, a chance to start afresh, to cast off the chains and shackles of the Old World, a beautiful kingdom bestowed upon us by God, and so on and so forth.

This sentiment was absent from that of the initial British settlers, largely being convicts, in Australia, at least for a good few decades. It may have been a New World to their eyes, but Hughes and most contemporary historians reiterate that the British only ever considered Australia little more than a jail, out of sight and out of mind. Settlers like Governor Macquarie would subsequently attempt to build, with the hope of creating a New World in Australia, albeit by destroying the existing one. But for the British settlers, Australia was a prison; its form natural, but its function now being designed. (Note: to a large extent, the American colonies had also initially been considered extensions of British prisons. Yet other aspects of colonialism came into play rather more than Australia, and indeed the British interest in Australia truly emerged once America had started rejecting British convicts en masse.)

“The space around it, the very air and sea, the whole transparent labyrinth of the South Pacific, would become a wall 14,000 miles thick”. [From The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes]

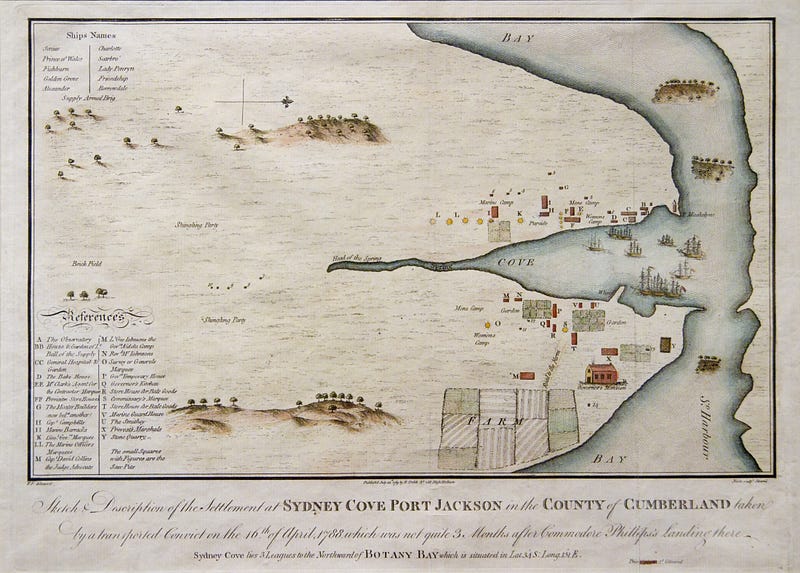

This 1789 map of Sydney makes the wall visible. The sparse settlement around the mouth of the Parramatta river and harbour of Port Jackson; the endless, featureless land to the west; the ocean, rendered almost as if a barrier itself, to the east.

Over one hundred years earlier than the Virginia landings depicted in Malick’s film, the Portuguese enjoyed a very different first encounter with the New World, apparently chancing upon Brazil when horribly lost attempting to sail around the coast of Africa (there are theories that they weren’t lost, but intentionally embarked on this route in order to get one up on Spain.) Peter Robb’s superb book, A Death in Brazil, draws from the letter of Pero Vaz de Caminha, deputed by the leader of the fleet, Cabral, to write back to Dom Joao II in Portugal. The meeting of the Portuguese and indigenous ‘Brazilians’ was apparently harmonious, and based around mutual wonder at each other. Robb describes Caminha’s letter as “the sole document of perfect poise in the history of the Old World and the New.” As with all documentation of the New World, the Old is amazed at the “perfect poise” between the natives and their environment:

Our Lord gave them fine bodies and good faces as to good men … they do not till the soil or breed stock, nor is there ox or cow or goat or sheep or hen, or any other domestic animal which is used to living with men. Nor do they eat anything except these manioc … and the seeds and the fruits which the earth and trees produce. Yet they are stronger and better fed that we are with all the wheat and vegetables we eat. [Letter from Pero Vaz de Caminha to Dom Joao II, 1500, from Peter Robb’s A Death In Brazil]

Robb, who is Australian, suggests that the “beauty of surroundings and the climate, the abundance of food and fresh water, and the untroubled relations with the extremely beautiful local people seemed, as much as the sheer glorious unexpectedness of this landfall, to create a little pocket of pleasure and refreshment out of time for Cabral’s thousand or so men.”

This “perfect poise” between Old and New Worlds did not linger beyond many subsequent Portuguese landings, and was certainly barely perceptible in most ‘New World’ discoveries since.

We can almost see an arc in the discovery of the New World here. Brazil’s abundance and beauty was broadly familiar to the Portuguese, but wonderfully richer, as if stretched and magnified but still recognisable. In 1609, Virginia’s humid mangrove swamps, testing weather and challenging soil almost saw off the English settlers, but it was still a broadly familiar environment, and with the help of the Algonquin, they survived. Australia, over a century later again, was an entirely new terrain altogether; utterly different to European sensibilities, leaving artists and writers clutching for reference points, and more damagingly, leaving the British officers and convicts bewildered and starving. The people were apparently not physically beguiling, at least not in the way Robb describes the naked Brazilians distracted the Portuguese sailor’s lingering eyes or, elsewhere in the South Pacific, Bougainville’s dreamlike encounter with beautiful Tahitian noble sauvages.

Perhaps the flora and fauna in Australia completed an arc away from Europe, towards an entirely New World, as if the European settlers had been ‘broken in’ gently with Brazil and America and then ultimately presented with something so environmentally challenging that it seemed barely possible that it was suitable for human habitation at all. At least, human habitation as understood by the British. Clearly, there was little understanding that this land had been inhabited perfectly well for far longer than European ‘civilisation’ could imagine.

Peter Conrad’s review of Tom Keneally’s latest book, in which the shock of the new is seen in reverse:

Keneally has more success presenting the story as sci-fi. To the Aborigines, the shiploads of bleached ghouls had erupted, like HG Wells’s Martians, through some ‘lesion in the cosmos’. And like the flesh-eating, blood-drinking Martians, their intrusion into a ‘biosphere’ where they did not belong instigated what Keneally calls ‘biological warfare’: a smallpox virus, to which the Europeans were mostly immune, killed off half the native population. When Keneally describes the colony as ‘virtual reality’, he might be identifying it with the matrix in the trilogy of films by the Wachowski brothers or with the space stations manned by asylum seekers in Blade Runner. [Peter Conrad review of Thomas Keneally’s The Commonwealth of Thieves in The Observer]

Joseph Banks was one of the principal botanists on Cook’s 1768–1771 voyage. He introduced eucalyptus to the West, and gave his name to Banksia, an indigenous Australian classic. Banksia adapts to the environment in ways which sometimes seemed unbelievable to Europeans:

Banksia plants are naturally adapted to the presence of regular bushfires in the Australian landscape. About half of Banksia species are killed by bushfire, but these regenerate quickly from seed, as fire also stimulates the opening of seed-bearing follicles and the germination of seed in the ground. The remaining species usually survive bushfire, either because they have very thick bark that protects the trunk from fire, or because they have lignotubers from which they can resprout after fire. In Western Australia, the first group are known as ‘seeders’ while the second ‘sprouters’. [Wikipedia]

Banks’s journals are one of the defining documents of Cook’s great voyage; they also depict the Old World’s amazement at the flora and fauna of the New. Banks and his fellow botanists struggled to keep up with the number of discoveries, and to describe this new land at all. Often it just seemed alien, as if the prism of the Old World refracted any discernible detail out of sight.

“1770 May 19: Countrey as sandy and barren as ever.”

Sometimes, this was all Banks would see, and write, staring at a land full of an entirely different nature, just as the later British settlers wouldn’t recognise the food offered by the terrain, nearly starving while indigenous Australians feasted.

“1770 May 3. Our collection of Plants was now grown so immensly large that it was necessary that some extrordinary care should be taken of them least they should spoil in the books.” [The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks, May 1770]

“1770 May 23… The Soil in general was very sandy and dry: tho it producd a large variety of Plants yet it never was coverd with a thick verdure. Fresh water we saw none, but several swamps and boggs of salt water; in these and upon the sides of the lagoon grew many Mangrove trees in the branches of which were many nests of Ants, one sort of which were quite green. These when the branches were disturbd came out in large numbers and revengd themselves very sufficiently upon their disturbers, biting sharper than any I have felt in Europe. The Mangroves had also another trap which most of us fell into, a small kind of Caterpiler, green and beset with many hairs: these sat upon the leaves many together rangd by the side of each other like soldiers drawn up, 20 or 30 perhaps upon one leaf; if these wrathfull militia were touchd but ever so gently they did not fail to make the person offending them sensible of their anger, every hair in them stinging much as nettles do but with a more acute tho less lasting smart.” [The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks, May 1770]

“Of Plants in general the countrey afforded a far larger variety than its barren appearance seemd to promise. Many of these have no doubt properties which might be usefull, but for Physical and oeconomical purposes which we were not able to investigate, could we have understood the Indians or made them by any means our freinds we might perchance have learnt some of these; for tho their manner of life, but one degree removd from Brutes, does not seem to promise much yet they had a knowledge of plants as we plainly could percieve by their having names for them.” [Joseph Banks, ‘Some Account Of That Part Of New Holland Now Called New South Wales’, August 1770]

The label on Rid insect repellent, as seen on Brisbane kitchen table:

RID REPELLENT

TROPICAL STRENGTH SPRAY

LONGER LASTING PROTECTION

against mosquitos that may carry

Malaria, Ross River Virus & Dengue

Neutral Scent

Repels Mosquitos, Flies, Ticks, Fleas, Leeches, Sandflies & Other Biting Insects

6 HOURS MOSQUITO PROTECTION

Books I’m yet to read but should have featured significantly in this post:

Peter Conrad’s At Home In Australia provides a history of the author’s country inspired by over 200 photographs from the National Gallery of Australia. (Conrad notes that the settlement of Australia coincided with the invention of photography.) Conrad wrote the superb Modern Times, Modern Places.

Tim Flannery — mentioned several times in Peter Carey in 30 Days in Sydney – has written several books about Australia’s environment: The Weather Makers: The History and Future Impact of Climate Change and The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People foremost amongst them. He’s also edited one of the classic First Fleet accounts; Watkin Tench’s 1788: Comprising: a Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay and a Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson. The raw text of Tench’s journals is available at Australia’s Project Gutenberg.

We didn’t get out of the cities, save for North Stradbroke Island, off the Queensland coast. Next time. There, the shock of the New World will really hit home. There we’ll discover the land described in Chatwin’s The Songlines, or in Voss, Patrick White’s nineteenth-century Australia through the eyes of a German emigré:

They were riding over the humped and hateful earth, which the sun had seared until the spent and crumbly stuff was become highly treacherous. It was, indeed, the bare crust of the earth. Several of the sheep determined to lie down upon it and die. Their carcasses did not have much to offer, though the blacks would frizzle the innards and skin, and stuff those delicacies down their throats. The white men, whose appetites were deadened by dust, would swallow a few leathery strips of leg, or gnaw from habit at the wizened chops. Their own stomachs were shrivelling up. In the white light of dawn, horses and cattle would be nosing the ground for any suggestion of leaf, any blade of grass, or little pocket of rock from which to suck the dew. The ghosts of things haunted here, and in that early light the men and animals which arrived were but adding to the ghost-life of the place.

“But it is what we expected”, the German assured himself.

[From Voss by Patrick White]

The sounds of birds and insects sound almost like a form of natural electronica. They are as delightfully alien to my ear as they must have been to the English settlers in Port Jackson.

Birds in Britain seem to operate mainly in the upper register — all tweets, warbles and chirps, helping conjure a gentle Englishness above all. German urban nightingales can break European noise regulations, and we can also talk of the musical avant-garde of the American birds, but these Australian birds are something else. They sound like a wildly imaginative compilation of the best ringtones ever.

I was woken by the rush of coffee from an espresso and a loud grating noise like a rusty hinge. Move your arse, called Sheridan, and I lifted myself up on my elbows, not too far, because this ledge at the back of the cave had a three-foot ceiling, and peered out through the grey feathery shrub. The rusty hinge grated again. Red-tailed cockatoos, explained Sheridan. He was standing at the table hacking into last night’s lamb. You’ve already missed the kangaroos. They’ve been and gone. Come on, mate, we’ve got to get back to the city … [From 30 Days in Sydney by Peter Carey]

Magpies here in Australia seem to be very different to the UK — more like a warbling, bubbling Susumu Yokota track. Crows, however, have the same horrible, brutish sound the world over. Murderous indeed. The Bush Stone Curlews are clearly related to their British equivalents, but more vocal still. I think Butcher Birds were also in the mix. And it took us ages to hear a Kookaburra, but it was certainly worth the wait.

But enough attempts at describing these noises. An ornithologist called Graeme Chapman has good selection of bird calls, so you can hear them yourself. The names of birds there are worth a visit alone. Looking at you, Spangled Drongo.

It never ceased to be delightful, incredible to see the likes of parrots and cockatoos flying around. Save the odd flash of colour on wingtips or breast, British birds seem decked out by Dries Van Noten, camoflaged for the green and brown trees and bushes of Northern Europe. Here, all kinds of colours flash through the trees.

On the ground, the cockatoo seems rather like a podgy mid-ranking colonial civil servant, wearing his white suit whatever the weather, puffing out his chest self-importantly and waddling around inspecting his empire. Oblivious, plovers stroll elegantly by, like elderly Victorian gentlemen, taking some air in the mid-afternoon. Bush-turkeys trot across the well-kept roads of the UQ campus, just around the corner from a patch of grass where magpies are known to dive-bomb trespassers. The Ibis is also all over Brisbane. An elegant bird, with a Venetian plague doctor’s mask of a beak, yet with an air of prehistory about it, particularly in that long curve.

It is a late-summer morning and I am painting and all I can hear are the cockatoos ripping the shit out of the trees above my head, and the cries of magpies, kookaburras, the bull at Mrs. Dyson’s, and amongst all this many smaller birds, orioles, honeyeaters, grass wrens, butcher-birds, the sweet rush of the wind in the casuarinas by the river … [From Theft by Peter Carey]

Robert Hughes on what bird-life British settlers would’ve seen and heard in 1788:

The density and range of bird life along the harbor was still amazing. Several dozen kinds of parrot thronged the harbor bush: Galahs, bald-eyed Corellas, pink Leadbeater’s Cockatoos, black Funereal Cockatoos, down through the rainbow-coloured lorikeets and rosellas to the tiny, seed-eating budgerigars which, when disturbed, flew up in green clouds so dense that they cast long rippling shadows on the ground. The Sulphur-Crested Cockatoos, Cacatua galerita, were the most spectacular — big birds with hoarse squalling voices, chalk-white plumage (dusted with yellow under the wedge-shaped tail), beaks the colour of slate, obsidian eyes, and an insouciant lick of yellow feathers curling back from the head. When excited, they would flirt their crests erect into nimbi of golden spokes like Aztec headdresses. These raucous dandies assembled in flocks of hundreds which, settling on a gum tree, would cover its silvery limbs in what seemed to be a thick blooming of white flowers, until, at the moment of alarm, the blossoms would re-form into birds and return screeching into the sky … The Galahs, smaller cockatoos, had gray backs, white crests and fronts of the most delicate, intense dusty pink, like the center of a Bourbon rose; so that a flock of them passing against the opaline horizon would seem to change colour — pink flicking to gray and back to pink again — as it changed direction, uttering small grating cries like the creak of rusty hinges. [From The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes]

And from Joseph Banks’s notes, on the voyage of the Endeavour in 1770:

The Land Birds were crows, very like if not quite the same as our English ones, Parrots and Paraquets most Beautifull, White and black Cocatoes, Pidgeons, beautifull Doves, Bustards, and many others which did not at all resemble those of Europe. Most of these were extremely shy so that it was with dificulty that we shot any of them; a Crow in England tho in general sufficiently wary is I must say a fool to a New Holland crow and the same may be said of almost if not all the Birds in the countrey. The only ones we ever got in any plenty was Pidgeons of which we met Large flocks, of which the men who were sent out on purpose would sometimes kill 10 or 12 a day; they were a Beautifull Bird crested differently from any other Pidgeon I have seen. What can be the reason of this extrordinary shyness in the Birds is dificult to say, unless perhaps the Indians are very clever in deceiving them which we have very little reason to suppose, as we never saw any instrument with them but their Lances with which a Bird could be killd or taken, and these must be very improper tools for the Purpose; yet one of our people saw a white Cocatoe in their Possession which very bird we lookd upon to be one of the waryest of them all. [Joseph Banks, ‘Some Account Of That Part Of New Holland Now Called New South Wales’, August 1770]

Sitting reading in the midday sun. You can hear the house ticking as it stretches out.

At night, the sound of the Brisbane interior is the fluttering whirr of ceiling fans and then geckos, noisily smacking their lips. Dusk looks serene, but the raucous exterior world of bats, birds and insects pervades either way.

Everywhere, all the time, the background hiss of cicadas— punctuated by the odd, rasping güiro percussion of those in the foreground—like a perpetually unwinding spring. There must have been other lizards and insects around too, as the noise was incredibly varied. There would’ve been toads and frogs though I didn’t see any.

In the sculpted UQ grounds — as much as any grounds can be kept ‘sculpted’ in Brisbane’s unruly, fecund foliage — we see a turtle resting on a grate in the middle of a lake, and an Australian Water Dragon. It was approximately 2 foot long, entirely still and soundless.

Within the seemingly constant noise, there is a respect for the established order of birdsong being pre-eminent in the morning, with insects taking centre stage in the evening. Is this some kind of mutually agreed broadcast schedule?

Of insects here were but few sorts and among them only the Ants were troublesome to us. Musquetos indeed were in some places tolerably plentyfull but it was our good fortune never to stay any time in such places, and where we did to meet with very few. The ants however made ample amends for the want of them. [Joseph Banks, ‘Some Account Of That Part Of New Holland Now Called New South Wales’, August 1770]

Just as space was drained of perspective by the random, flickering transparency of the trees, so it was hard to guess where sounds originated. The throbbing croak of the cicada on a branch ten feet away might seem to be coming from all around … [From The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes]

The house in Brisbane, surrounded by tall trees and bushes, was apparently a popular destination for bats — here called Flying Foxes. Late one night, watching Liverpool against Chelsea in the FA Cup semi-final beamed live from a sunny English afternoon, their noise was incredible, sometimes like water squeaking down the drain, all Donald Duck-like rasps and squalls. At other times, quite unbelievable screams. Who knows what they get up to?

Walking through Sydney after dark, the silhouettes of flying foxes swoop above the streets from time to time, wings smacking the trees, another reminder I was elsewhere. They’ve taken to hanging out amongst the ancient trees of the Royal Domain Park, Sydney. They’re potentially damaging them, so are being shoo-ed away somehow (chemically?). (Ed. A decade on, a recent visit confirmed they’re no longer there.)

Perhaps as a result, they alternate between attempting to casually hang upside-down, like giant bruised fruit, and then suddenly fly around, screeching in a disturbed fashion. Kids look up in awe, emotions scuttling across their faces — terrified, delighted, fascinated all at once.

The one time they didn’t make noise, legions of them were flying noiselessly overhead over our house in Brisbane, heading for the colony at Mount Coot-tha behind us. Thousands must have flown by, squadrons high in the night sky. What if they suddenly decided to attack, peeling out of formation and screaming down towards us like Stukas? We wouldn’t stand a chance.

Dinner at a friends. He’s an architect, and has designed a fabulous double-height space at the front of the floating house in Brisbane, where we’re sitting down. The house subscribes somewhat to the school of thought embodied in the ‘Jack Ledoux’ character in Peter Carey’s 30 Days in Sydney

His notion of a house is a campsite. He likes it best when there are no walls at all, and his houses are made in the tension between his desire to be open to the elements and his clients’ desire for protection from them.

In the sub-tropical Queensland climate, foliage can be so lush, even in drought conditions, that urban areas can be overgrown, engulfed, inside and outside at the same time. The weather is generally either hot or warm all year round, with only regular downpours to deal with. Thus, the architecture often adventurously dissolves and blurs, as a result.

Back to dinner, and that double-height living space … at the apex of which, two geckos perform noisy, high-wire sex, almost as if for our entertainment as well as theirs. Somehow conjoined, end on end, they thrash about frenetically, 12 metres above our heads. As T. commented, the danger must spice it up for them … Our host shoos them out the front window with a giant inflatable children’s toy. Coitus interruptus.

Carey quotes Anthony Trollope in 1872:

I despair of being able to convey to any reader my own idea of the beauty of Sydney Harbour … I can say it is lovely but I cannot paint its loveliness.

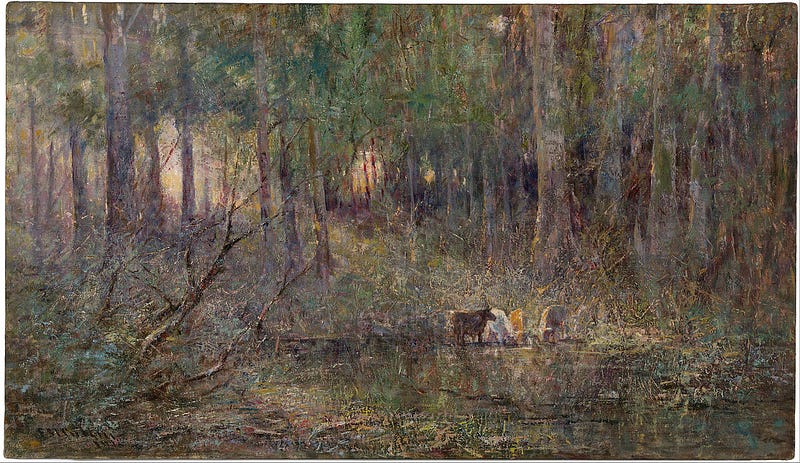

Many Western artists during and since this time have wrestled with the problem of representing Australian terrain. It often seemed nigh-on impossible when Australian art was labouring under the twin yokes of the colonial tradition optimised for European arcadia and the ‘cultural cringe’ picked apart in Robert Hughes’s essay “The Decline of the City of Mahagonny”.

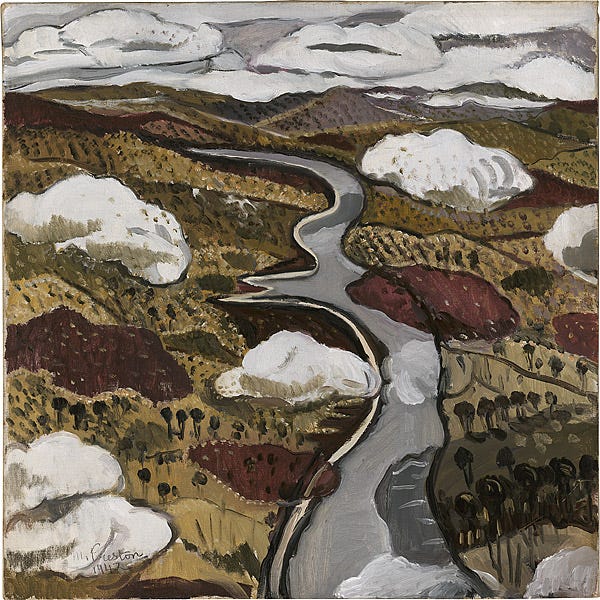

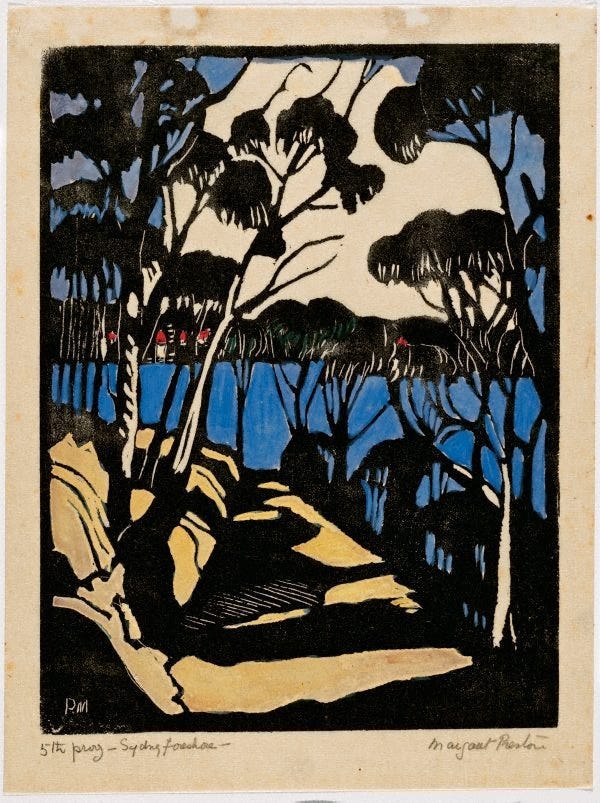

We saw evidence of these attempts — and their more successful successors — at excellent exhibitions at the Queensland Art Gallery (Brisbane) and National Galleries of Victoria (Melboune). The interior ‘red land’ was often the focus, a magnetic pull for artists attempting to find entirely new methods for depicting the strange space, textures and colours. The Australian Collection at the NGV Australia reveals beautiful early attempts at this by Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Frederick McCubbin and others.

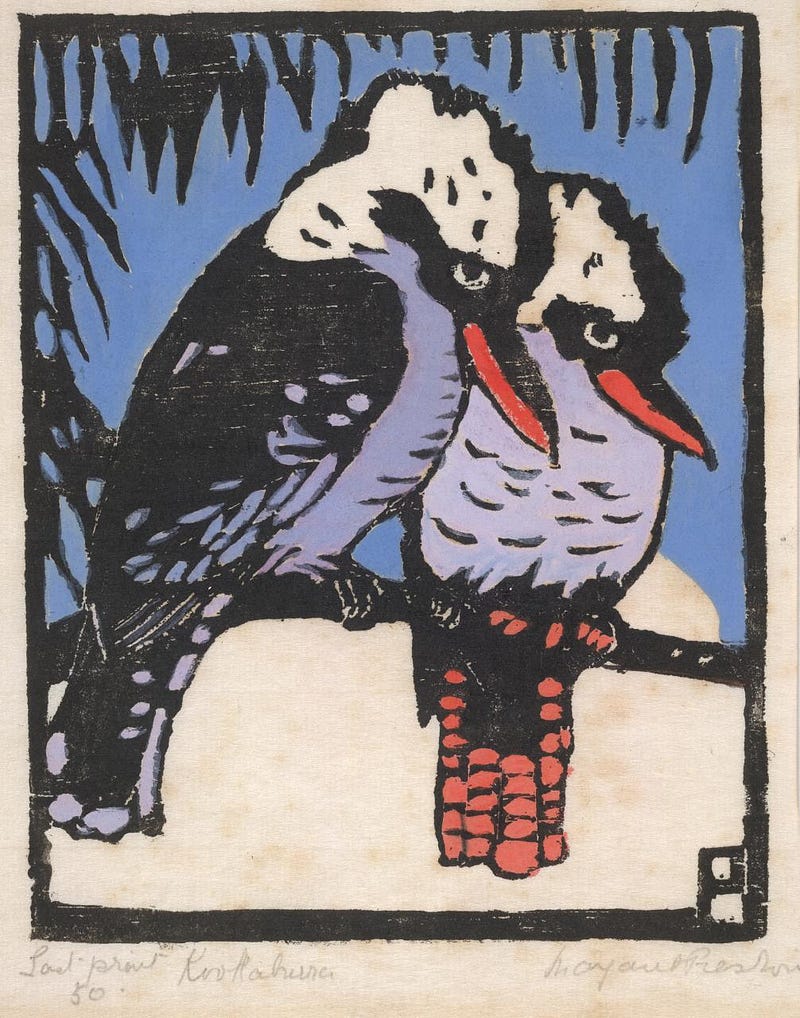

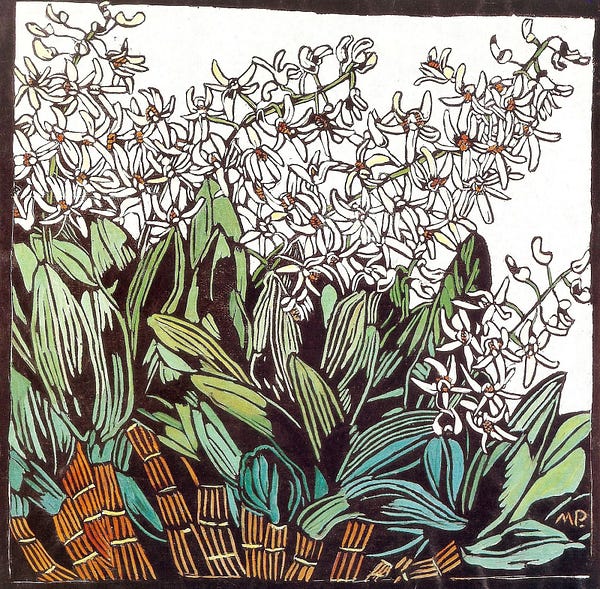

I saw glorious work by later artists, in particular Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington-Smith — revered in Australia but barely recognised in the ‘Western art world’ — at a fabulous show at Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane. Preston’s woodcuts of flowers and bushes and Cossington-Smith’s landscapes are particularly relevant to this theme of interpreting Australian flora and fauna.

Later artists at NGV Australia are also largely names new to me, despite my interest in art — my ignorance, Western art’s ignorance, or sheer distance? — and many stand out as great painters, particularly Fred Williams, Albert Tucker, Roland Wakelin, John Brack, Jon Cattapan, and Jeffrey Smart. All producing a form of Australian art via a fractured Western tradition, relocated and reimagined.

The work of Fred Williams truly takes on the interior Australian terrain as I imagine it. (The Picador edition of Chatwin’s The Songlines features one of his ‘Red Landscape’ series.) These works reassure that painting itself can be an appropriate response to this environment; whether other art forms are more appropriate is another thought for another day.

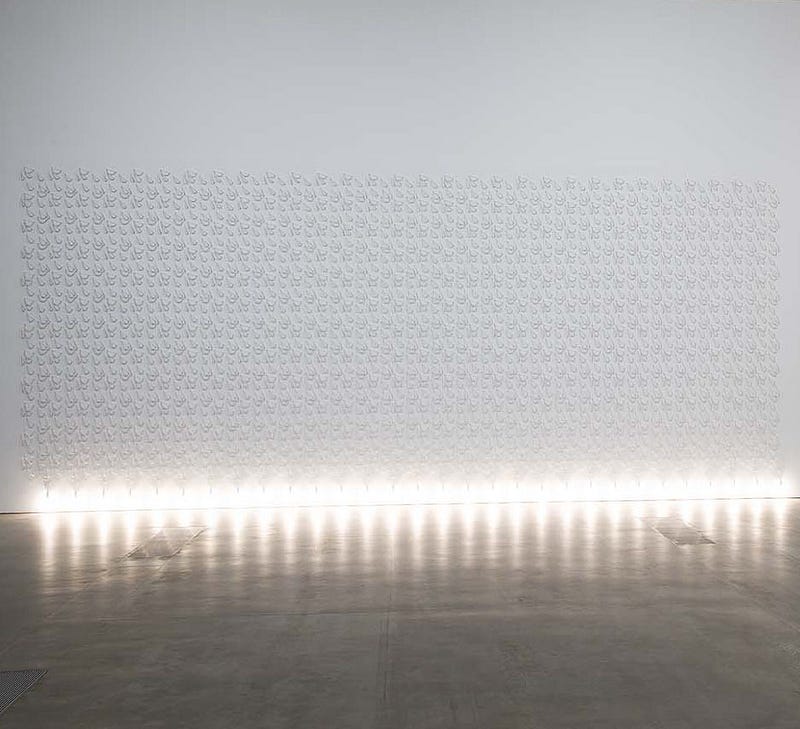

Obviously, indigenous art has fewer issues of representation of the Australian land. If you’re in Melbourne, view the superb collection at the NGV Australia, including well-known indigenous artists such as Emily Kngwarreye and Rover Thomas. Although Albert Namatjira is perhaps best-known of the early generation of indigenous artists, the more abstract work — both ‘traditional’ and contemporary — resonates more with me. There’s some unutterably beautiful painting and sculpture here, and also in an exhibition of contemporary indigenous art I saw at QAG, especially the work of Jonathan Jones.

In general, this was a trip to the cities, which cling to Australia’s coastline like barnacles on the hull of a ship, or as if repelled magnetically from the centre of the country. (In The Songlines, Bruce Chatwin notes the geography of the modern country might have been very different if settled by a people who were comfortable with great expanses of space. Not the English, but the Russians, perhaps.)

Given this, the actual flora and fauna encountered were Australian Urban, rather than the Australian fauna of children’s books. So absolutely no crocodiles, wombats, kangaroos, koalas, platypus, or any of the more exotic creatures foreigners associate with Australia. All I saw of a possum was its furry arse poking out of the Moreton Bay Fig that it had burrowed its head into, trying to have a kip. The emblematic Boab trees were only really seen in parks. The Australian flora of the bush was witnessed only in Margaret Preston’s gorgeous woodcuts and paintings.

However, even the Australian Urban flora and fauna is still extraordinary to European eyes. Trees like the Poinciana — with its dried pods usable as percussion instruments — are glorious; ‘blooming’ is almost not effusive enough a description for when they’re in flower. In general, the trees are rich, lush and evergreen in sub-tropical Brisbane, full of flowers. In Sydney and Melbourne, they’re more recognisable as trees at first glance of Western eyes, with introduced species alongside the eucalypts, no doubt obliterating the indigenous population.

On a trip to the Gold Coast, the quite repellent ‘bugs’ can be seen in a fish shop. Three burly men sit on a picnic table outside, shovelling the dripping innards into their face, chubby fingers scraping the juicy flesh from the exoskeleton of these horrific creatures, which appear to be the offspring of David Cronenburg and HR Giger.

A snake is spotted on the driveway, departing the scene rapidly. I didn’t see it. I didn’t see any snakes, save for some encased monsters in museums. I have a feeling that quite a few saw me. The undergrowth seems constantly quivering. Hughes describes how, for the British invaders, “nothing about Australian animals was obvious … the landscape was alive, but secretively so.”

And yes, spiders are everywhere, and to a North European’s eyes, bloody big ones too; webs stretch across lampposts, over your head; at the toilet to Bill’s in Sydney, a beauty sits on the fern outside. Again, I saw quite a few, but how many saw me?

Around Brisbane and Sydney, I see an entirely new kind of tree. The Moreton Bay Fig — they’re like an entire jungle helpfully compacted into a single tree. Branches, and even other plants, sprout out of the main trunks and then perform a time-lapsed arcing dive, draping down towards the ground, where they become supplementary trunks, acting as struts to support the tree’s growth. Thus, the Moreton Bay Fig ends up with multiple trunks, which bend around and melt into one another, around which a dense cascade of branches and roots twist and turn. It’s a rainforest tree, and water-hungry, so they’re often fenced off, but we see several disdainfully uprooting pavements in New Farm.

The Melaluca — or Paperbark tree — is also a new favourite. You can peel off the wonderfully soft bark, which has a pinkish hue to the light brown papery skin. It feels like parchment, and crumbles into dust if you rub it between your fingers. We see forests of it at North Stradbroke Island, heading down to the sea, and unruly copses of it surrounding James Birrell’s fabulous concrete UQ buildings.

The various Gum trees are more delicately lovely than expected. Sinuous silvery limbs, elegant and lean, stretching upwards at length. As Hughes puts it: “Not evergreens, but evergrays: the soft spatially deceitful background colour of the Australian bush, monotonous-looking at first sight but rippling with nuance to the acclimatized eye.” (These lovelies below are from the rather more lush Brisbane.)

Peter Carey’s 30 Days in Sydney is a cracking little book, in which the author, very loosely, describes this built-up city of 4 million through natural motifs:

Sydney was like no other place on earth, and it was defined not only by its painful and peculiar human history but also by the elements: Earth, Air, Fire and Water. [From 30 Days in Sydney by Peter Carey]

The city’s setting is utterly stunning — certainly the most beautiful I’ve ever seen — but the elements are still a dominant factor of the urban experience. Peter Conrad, reviewing Carey’s book, noted Sydney’s “bullying blustering wind (euphemised by the locals as a sea breeze), the treachery of its waters, the menace of circumambient bushfires.”

Carey deconstructs the city through both these elements, and the man-made layers of matter that Sydney is built upon, having witnessed a fantastic lecture from architect Peter Myers on “The Three Cities of Sydney”. And then from the middens of shells at Bennelong Point, under Sydney Opera House, to the sandstone that defines Sydney harbour:

These bright yellow cliffs show the city’s DNA — that is, it is a sandstone city, and sandstone shows everywhere amongst the black and khaki bush, in the convict buildings of old Sydney and in the retaining walls of all those steep harbour-side streets. Sydney sandstone has many qualities. It is soft and easily worked (to the convicts a sandstone was a man who cried and broke beneath the lash). It is also highly porous, and the first settlers would use it to filter water. When it rains in Sydney, which it does as dramatically as a Hong Kong monsoon, the water drains rapidly, leaving a thin topsoil from which the nutrients have long ago been leached. This in turn determines the unique flora which thrive here.

With nutrients so scarce, Tim Flannery writes, plants can’t afford to lose leaves to herbivores. As a result they defend their foliage with a deadly cocktail of toxins and it’s these toxins that give the bush its distinctive smell — the antiseptic aroma of the eucalypts and the pungent scent of the mint bush. When the leaves of such plants fall to the ground the decomposers in the soil often find it difficult to digest them, for they are laden with poisons. The dead leaves thus lie on the rapidly draining sand until a very hot spell. Then, fanned by searing north winds, there is fire.

For 40,000 years Aboriginal hunters and gatherers had known how to eat, to sometimes feast here, but the British who began their creeping invasion in 1788 had no clue of where they were. They set out to farm as they might in Kent or Surrey and the sandstone nearly killed them for it. Starvation. That is what the yellow cliffs of Sydney spell if you wish to read them. [From 30 Days in Sydney by Peter Carey]

Joseph Banks sees the terrain of New South Wales in 1770 thus:

For the whole length of coast which we saild along there was a sameness to be observd in the face of the countrey very uncommon; Barren it may justly be calld and in a very high degree, that at least that we saw. The Soil in general is sandy and very light: on it grows grass tall enough but thin sett, and trees of a tolerable size, never however near together, in general 40, 50, or 60 feet assunder. [Joseph Banks, ‘Some Account Of That Part Of New Holland Now Called New South Wales’, August 1770]

Again, Banks will not have realised that the trees were spaced this way to enable agriculture—albeit just not as the British recognised ‘farming’, perhaps for their own malevolent reasons—and to flush wildlife out of the bush for hunting, whilst preventing a build-up of fire-load, avoiding uncontrollable fires.

The rocks on the coastline around Sydney from Bondi to Bronte look volcanically formed, pock-marked, lunar and twisted into sharp primitives. It’s more likely they’re shaped by the ocean’s proximity but they’re quite startling either way.

The rocks further up the coast in Queensland, on North Stradbroke Island, are even more extraordinary. Walking around the beaches, I find several different patterns of rock; they’re sharp underfoot and, standing over them, have the texture of satellite photos of Middle Eastern deserts. I’ve never seen anything like this, either.

Melbournians talk of the ice chill from the southerly wind — of the Antarctic — versus the scorching dry heat of the north-westerley — from across the desert interior of Australia. Carey in Sydney hates the “the westerley” in particular. Another character in his book talks of “the southerly”, having barely lived through one whilst caught out at sea on his skiff … and then, rather suddenly, not in the skiff but being tossed around by 12-foot waves. Perhaps it’s because they’re on the ocean, with a mountains and deserts to their backs, but people in these cities seem very aware of the patterns, cycles and directions of wind, more so even than in weather-obsessed Britain.

These storms always begin from the south-west. Then they slowly shift around to the south, then to the south-east and then over the next few days they break to the east and the north-east. And when, finally, the wind shifts to the north-west you know the cycle is setting itself up again. That’s the summer pattern in Sydney. [From 30 Days in Sydney, Peter Carey]

Pittwater, as described by Carey, sounds like Stradbroke Island. He sets out on a skiff with his mate, and looks ashore: “Pittwater is a kind of paradise with its little coves, inlets, mangroves and the forests of glistening silver-trunked eucalyptus which come right down to the water. You could not look into this bush without imagining the past.” Stradbroke’s beaches are hemmed in by eucalyptus and sharp rock, but also by what seem to be ancient melaluca rainforests. To me, the past was all too present there, but it wasn’t the human past as much as Jurassic. The dense, lush, waist-high undergrowth almost glowing green in the fierce light, tropical flowers blooming amidst the fern, dragonfly hovering and darting. So yes, the past, but you expect a Velociraptor to emerge as much as wary Quandamooka person or starving, desperate convict.

The beaches of Australia have been described a million times elsewhere — suffice to say I’ve never seen anything like the beaches in Queensland and Sydney.

There’s a difference even there. Sydney’s are enclosed in perfect circular bays — “like the best of Greece and Cornwall rolled in together”, as Drusilla Modjeska has it in her book Poppy. The Queensland beaches are long-limbed stretches right up the coast, perfectly empty save for us, perfect sand, perfect blue glassy rollers, perfect.

Brisbane, early-April. I’m invited to play a game of ‘touch’ rugby at 6 in the morning, before the other players head off to work. I’m drenched with sweat within 5 minutes. That’s 6.05. It’s already hot. I haven’t played rugby for 20 years, and even then I’d only played a handful of times, at school in Sheffield. It was more of a football school and I was more of a football player. However, as running around after footballs have been a firm fixture in my life, after a few haphazard interventions I take to the game OK. What I’m not ready for is the heat and humidity, even at that unearthly hour of the morning. It’s practically the middle of the night and I’m gasping for air and wiping the sweat from my brow so it doesn’t run in my eyes and prising the borrowed t-shirt off my chest to create some kind of airflow. Truly amazing. It’s actually good, when you catch your breath. It won’t be for some months later — until I’m in a sauna in Helsinki — that I feel a similarly thick, hot, damp air filling my lungs.

The humidity in Brisbane, as well as the directness of the sun, differentiates it clearly from Sydney, and certainly from Melbourne. The latter’s climate is generally described as “Very European” — which is true as long as the subset of Europe you’re referring to is the Deep Med. It hits 35 in summer no problem. It’s not really the slate grey screensaver skies of the Northern European climate I’m used to. It feels like a city with seasons; a good balance between sizzling heat and occasionally being allowed to wear a scarf in winter without accusations of affectation.

Up the coast, Sydney has it all. Most days are gloriously sunny; that’s all you need to know (almost). There’s more detail on the intricacies of the Sydney climate in Carey’s book — the winds, the squalls — but it seems poised perfectly between Melbourne’s seasons and Brisbane’s sub-tropical permaheat. Even with the Brisbane sun set to ‘autumnal’, it sometimes feels like the conditions are spiralling inexorably towards JG Ballard’s The Drowned World.

Brisbane, walking, midday. 34 degrees and 93% humidity. To call this ‘Autumn’ is an inversion of the word indeed, like the swans here are black not white, like the coriolis effect. The streets around West End are very empty. Something about mad dogs and Englishmen springs to mind. Taking my sun hat off feels good, letting the hot sun dry the wet hair plastered to my head. But it’s not advisable for long. I put my hat back on, only to take it off again in a bit. I feel like one of those lizards that alternates its standing feet on hot sand. But with a hat.

It’s gloriously hot. The same temperature as that I felt in Tunisia once, but here the air is thicker with humidity, something you can feel as you move through it. Almost as if the air itself possesses a slight resistance. And this is Autumn.

Don’t call it ‘the sea’ in Australia; it’s the ocean. People will pick you up on that. They’re proud of the Pacific, it’s size, power, beauty. At Bondi, events are conjured up by the ocean as if casual reminders of its power.

The force of the ocean gives it an exciting, vaguely dangerous air. The impression is not exactly false. Can you see that enormous rock just off Ben Buckler, the northern headland of Bondi Beach? It was not there on July 14, 1923. Next day it was delivered to the beach like a piece of flotsam. It weighs 235 tons. [From 30 Days in Sydney, Peter Carey]

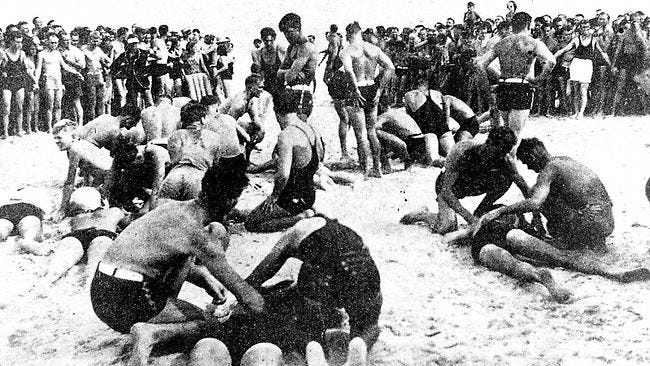

Another reminder in 1938. 35,000 people on the beach — suddenly 3 big rollers sweep in and the resulting riptide pulls most of those thousands way out into the ocean. Amazingly, only 5 died, thanks to the efforts of the lifeguards.

In the surf at Stradbroke, off the Queensland coast, you can feel it’s an ocean, not a sea. When the water gets slightly ‘dumpy’ — which might mean something altogether different in polluted English water — the Pacific’s waves will just turn you upside down and then follow-up with a smack round the head, in a classic one-two combination. This leaves you momentarily without air, apparently entombed in a wall of water. And that’s when the undertow starts to pull your legs — if they’re still underneath you — or all of you, if not — in a direction which you can only guess isn’t back to shore. Quite a feeling. As this is in the safe bit of the beach, between the flags, you’re OK; the waves aren’t enough to leave you entombed in water, and you burst up through the surface, gulping in the warm air. Again, this is the safe bit of the beach; the Pacific is just messing with you. You wouldn’t stand a chance if it got serious.

Hughes entitles one chapter of The Fatal Shore, ‘The Geographical Unconscious’ …

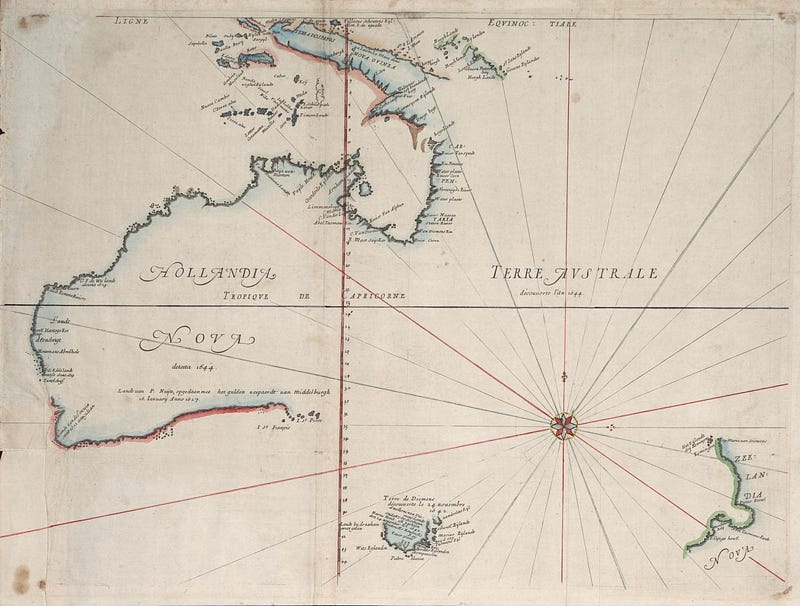

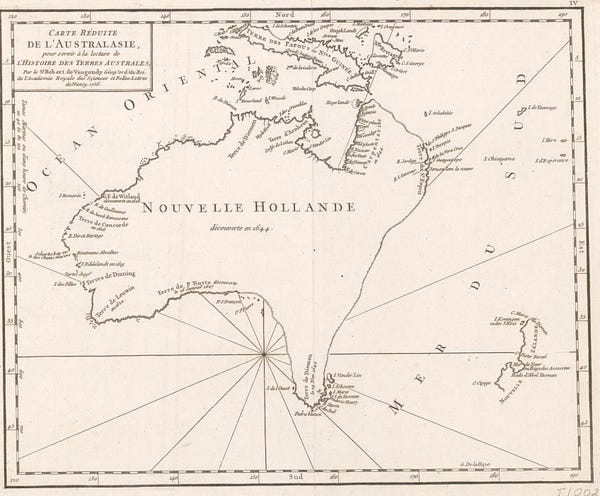

Pomponius Mela, the earliest Roman geographer, postulated in AD 50 that there simply must be a ‘terra australis incognita’ — an unknown southern land — as much to ‘balance’ the northern land mass above the equator as anything. From that point on, numerous explorers attempted to find this land, cartographers nibbling away at the coastline until the French, Portugese, Dutch and English sailors of the 17th and 18th centuries truly begin encircling their prey.

Cook encounters what would become New South Wales by accident as much as design, having nearly given up.

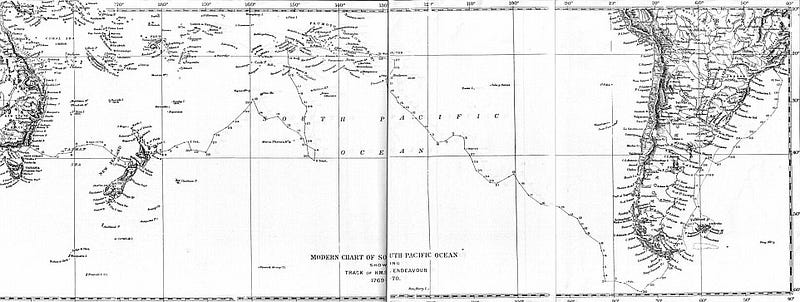

The Endeavour chart, indicating the journey across from New Zealand towards the lucky northwards drift — just past the words ‘Tasman Sea’ — enabling the colonist’s discovery, and subsequent invasion, of the East coast of Australia.

Despite the inauspicious beginnings, contemporary Australian culture is now synonymous with food, ironically enough. Glance through the obsessively produced pages of the Australian edition of Vogue Entertaining & Travel or Gourmet Traveller magazines, say, or weigh up the number of Australian cookbooks lining the shelves. The climate — essentially Mediterranean along the South coast and warmer and Asian up the East and West — now provides food in abundant quantities, offering up the kind of ripe and full vegetables, for instance, that I’d only ever seen in Tuscany and Provence street markets. The meat is of the highest quality and the fish and seafood is incomparable, generally cooked for a highly sophisticated palette, drawing flavour from the entire South-East Asian region. The wines of Australia and New Zealand now effortlessly trounce their ‘Old World’ counterparts, having enacted a tectonic shift in the global wine producers’ market over the last 20 years.

It’s an exciting time for the Australian food scene, with our fresh produce getting better and better all the time! [Australian Vogue Entertaining + Travel, Autumn 2006]

In 1790, this future harvest would’ve seemed utterly impossible, a cruelly insane mirage.

On the way towards today’s Australian food culture, from those early starvation years, the colony witnessed a curious response to the available food of the land. Even given an understanding of how to live and eat well from the local environment around New South Wales, the desperate class structures erected by the settlers meant that exploiting the increasingly understood flora and fauna was suppressed in favour of an attempt to recreate British food on the other side of the world.

The desire not resemble convicts even affected diet. (Louisa Anne) Meredith was puzzled by her hosts’ refusal ever to serve fresh fish at lunch or dinner, despite the superb quality and variety of Sydney seafood. Instead, she was given smoked salmon or dried cod brought from England. This aimed to invert the convict diet. Convicts traditionally ate salted meat — which signified lack of property, for only the landed could enjoy fresh beef or lamb — and fresh fish. The ceremonial food of the free must therefore be fresh meat and salt fish. [From The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes]

Peter Robb notes the same phenomenal silliness in that earlier New World, Brazil. Again, abundant local produce ignored in favour of imported bacalhau.

Taking salt cod from the North Sea via the Mediterranean across the Atlantic and across the equator to Brazil was an even greater improbability, and the farther the bacalhau got from where it started the less cheap it became. As a preserved food it was just as resistant in the tropics — but who, living on the tropical South Atlantic, needed to preserve fish for more than a few days?

There was a parallel here. Australia’s early colonial life and its insecurities, later but not unlike Brazil’s offered some clues. A genteel visitor to Sydney in the early nineteenth century was struck by never being served fresh fish or seafood, amid a plenty like Brazil’s, only salt cod and smoked salmon. The meat was fresh, from her landowning host’s own livestock, the fish never. Fresh meat was a landowner’s luxury — convicts ate salt beef and hardtack or xarque — but anyone could throw a line into the waters of Port Jackson and take home a splendid fish dinner. Not to mention the oysters covering the rocks. The only way of asserting your social standing when it came to eating fish was to stick to expensive and inferior preserved fish shipped across the globe from home. I think it was the same in Brazil’s North-east. Whites liked to remind themselves they were Portuguese and fidalgo, and clung, after centuries, to the old ways. The common forms of meat in Pernambuco were dried xarque and carne de sol. Fresh beef or kid was costly and unusual. Fresh fish was everywhere, but bacalhau was imported and recherché enough to count as extracivilized, and far too expensive for most people to afford, especially the descendants of slaves. Discriminations in the kitchen matched the vaster ones in the streets. [From A Death In Brazil, by Peter Robb]

Night on North Stradbroke Island. We’re standing outside our prefab shack (Ed. Which I later realise was designed by Donovan Hill architects.) Squadrons of flying foxes are performing fly-bys up and down the road. The night sky is as clear as I’ve ever seen it, and composed of entirely different constellations. Some overlap — I can see Orion, but upside-down? — but generally I’m standing under new stars. The noise in the trees around us is immense. The canopy of stars seems propped on walls of cicada-encrusted paperbarks. Here we feel enclosed by nature. Truly wondrous.

Ed. Originally published at cityofsound.com on July 16, 2006

Leave a comment