An adaptive city reforms from within

Wandering around Barcelona over Christmas, 2005, I was much taken with La Ribera and El Born districts, which comprise a major part of the Old Town, or Ciutat Vella. With a history extending over a millennium, this is essentially the heart of the city. Or the stomach perhaps. Either way, there can be few examples of the medieval European city in such fully working order, still brimming with people, noise, smells, trade of all kinds. In fact, it makes no sense to describe it as ‘medieval’ at all, given the ease with which it also sits within the 21st century. It’s capable of flexing form and fabric to accept change apparently effortlessly, providing a showcase for contemporary architecture dated 1328, 1500, 1870, 1908 or 2005.

The density in Ciutat Vella is such that you almost feel contained within some kind of stone organism. You emerge into the neighbouring Eixample almost gasping for air, blinking in the light, breathing in the wide open 19th century boulevards. And yet, back towards the Mediterranean, we’ll see that history suggests this tightly wound, virtually solid city space is almost as effective and adaptable as Cerdá’s Eixample plan. The form of El Born is such that modular design solutions can be enabled by simply punching holes in blocks to enable sudden impromptu squares. One can almost imagine the skin healing over again given time, slowly filling these gaps with people and concrete … until it’s time to punch another hole somewhere else. As if each block truly is part of some greater, living whole. The built fabric in this part of the city is more like a membraneous, textured skin rather than streets, blocks or roads.

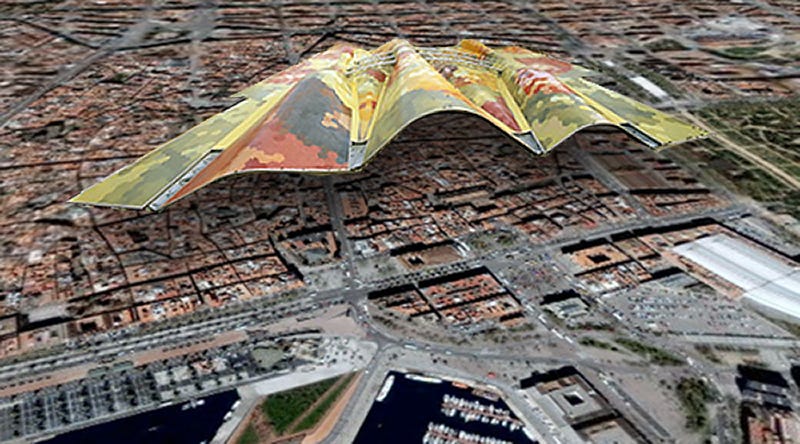

In fact, the form of some contemporary Spanish architecture, especially Miralles’ Mercat Santa Caterina in between La Ribera and El Born, appears to (unconsciously?) echo these earlier constructions. Mercat Santa Caterina has a colourful skin stretched over tightly-packed individual plots within, almost as if it were a fractal suggestion of Ciutat Vella itself. The density of El Born behind the market is such that it’s not hard to imagine Miralles’ reptilian roof continuing to stretch and sweep overhead, occasionally punctured to let light and space in but ultimately re-forming to ensure this part of the city is preserved into the future. Not untouched by change, but adapting organically to it.

Given this density, the effect of removing a block can be dramatic, beautiful and useful. In Topic magazine’s city edition, David Haskell’s editorial notes the ghostly interior lives laid bare by this punctured structure. Haskell describes an urban archaeology made possible by this coincidental exposure (and particularly the inadvertent collages of tiles, a form of decoration particularly associated with Barcelona). What Haskell highlights most of all is that these ghost traces indicate that these were lived spaces.

Carved out of the dense fabric of Barcelona’s old city sit pockets of open space in development purgatory. Chances are they won’t be there for long, thanks to an aggressive municipal campaign to improve public places, and to a corresponding increase in private market pressures. Their futures uncertain, the pockets presently range from fenced-in construction sites to paved lots perfect for a pickup game of futbol. And as for what used to be there, the past is written on the wall … Building collages capture an essential paradox of the city: they are, in both senses of the word, vital. They are both delightfully so, and necessarily so. They make Barcelona unexpectedly thrilling, especially for the majority of tourists who will return to a less vibrant hometown. But the collages also testify that Barcelona is essentially lived, not visited — it is at heart a collection of people, with specific needs and desires and ambitions and memories and friendships born of circumstance. … Gaudi’s most valuable gift to Barcelona was not the soaring Sagrada Familia … rather the example of how a city can modernize while retaining its locality, personality and whimsy.

Here are three shots of such a “pocket”, discovered over Christmas (and where I think it is in El Born):

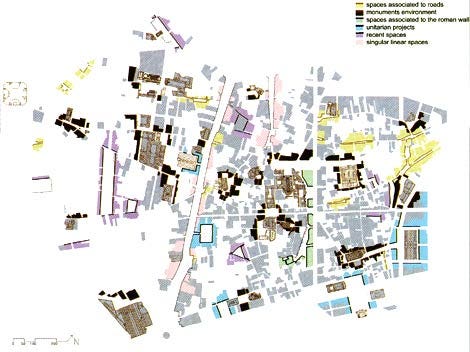

Despite the rising prices in Spain’s most expensive city, this is still a genuine mixed-use, mixed-occupancy neighbourhood, and despite Haskell’s (possibly valid) concerns about “private market pressures”, it continues to be so. So we zoom out from these punched pockets amidst the “vital”, lived city blocks, to observe the ancient district itself, full of personality indeed. Yet just as Miralles’ market isn’t simply pure organic development, neither is this city space as essentially unstructured as it might appear. Joan Busquets, in his book Barcelona: Evolution of a Compact City notes that many of these forms and patterns date back to the 13th century (exemplified by, say, Carrer Montcada). There are various clearly articulated theories of urban development back to this time too, especially by Francesc Eiximenis in the late 14th century.

However, when the densification of areas around Santa Caterina and El Raval in the mid-19th century resulted in population levels of 850 inhabitants per hectare, one of the highest in Europe, the tactic of punching holes in the fabric was deployed regularly. Squares and promenades have repeatedly been opened up and knocked through since the 18th century, on a large scale (e.g. Passeig de Gràcia; Plaça de Sant Jaume; Plaça Reial; ultimately the Cerdà plan, including the Eixample; then Via Laietana) or on the micro-scale of the individual block.

Into the 20th century, as formalised urban planning develops beyond Cerdá, the tactic gains a more formal description accordingly. After the Le Corbusier-influenced GATCPAC thinking in the 1930s, “opening up the district” describes the creation of new squares by demolishing streets in the Raval and Ribera specifically (e.g. Plaça George Orwell. Ironically, this tactic now also has a home in the more ‘modern’ Eixample blocks, with the recovery of internal courtyards, which had always been planned but rarely fulfilled.)

This urban change — a “reform from within” according to Busquets — is fascinating to observe, and to him indicates Barcelona’s unique talent for enabling simultaneous development at differing scales, again in an almost fractal sense — from opening up a square up to the special projects of the 1992 Olympics. He sees the last 160 years characterised by constant ‘reform from within’ tactics, which can be classified simply as streets either opening up, or lines of buildings drawing back, or squares or gardens created by demolishing an urban element, and “very often recycling parts of existing facilities”.

Given that these last two centuries of modernisation in the old town can be essentially described as “thinning out the compact fabric”, it’s incredible how dense the place still is. The Ciutat Vella still feels tightly interwoven, and one can only guess that as each new ‘breathing-hole’ is punched through, another section might fold back in on itself.

Creating the Eixample as the locus of development — effectively, a positive distraction — meant that this old centre avoided the tampering suffered by Paris and London. Yet after this virtual abandonment by planning and real-estate sectors in the second half of the 20th century, the Ciutat Vella has retained its relevance. In Busquets’ words: “In short, the structural keys of the city once again hinted at a whole body of potential in Ciutat Vella that had been overridden during phases of frenetic development and abuse.” So did the form of Ciutat Vella enable an adaptation to change, or did it just lie low until its strategic position was realised?

Formally, the Eixample is the aspect of Barcelona most frequently lauded for its adaptability through regular pattern. In adaptive design, whatever the medium, it’s often easier to work with interlocking blocks. Indeed Busquets talks of the Eixample’s “morphological adaptability of the square grid with chamfered corners” and notes that:

“The rigour of its geometric order has enabled the production of an urban element in which a wide variety of urban uses have been installed with admirable architectural flexibility: the Eixample is an ongoing laboratory of architectures that has room for the most diverse styles and trends, all within the general coordinates of alignment and ground levels established almost from the very start.”

Absolutely true, and an undoubted prima facie example of an adaptive architecture at the urban block scale.

However, looking seawards, the adaptability of the earlier Ciutat Vella also gives us pause for thought — that facets of adaptive design might also include a sheer density of architecture, with highly variegated form, within a malleable fabric capable of taking a punch from time to time, recycling itself further within strategically orientated spaces which retain relevance over centuries. The “reform from within” of the Ciutat Vella indicates that this old city will continue to adapt, to roll with its own punches, despite its apparently haphazard, ‘whimsical’ form. It too presents us with a “laboratory of architectures”.

Ed. This piece was originally published on 19 February 2006 at cityofsound.com.

Leave a comment