Representing cities beyond the satellite image

Descending through the artefacts, Powers of Ten-like, we pause finally, hovering above the city, rapt with attention. I could spend all day exploring this Google Earth, but it strikes me that there’s a couple of extensions I’d like to see. Neither of which are easy, but why should that stop idle speculation? (This piece was originally published at cityofsound.com on 29th January 2006, around six months after the mainstream release of Google Earth.)

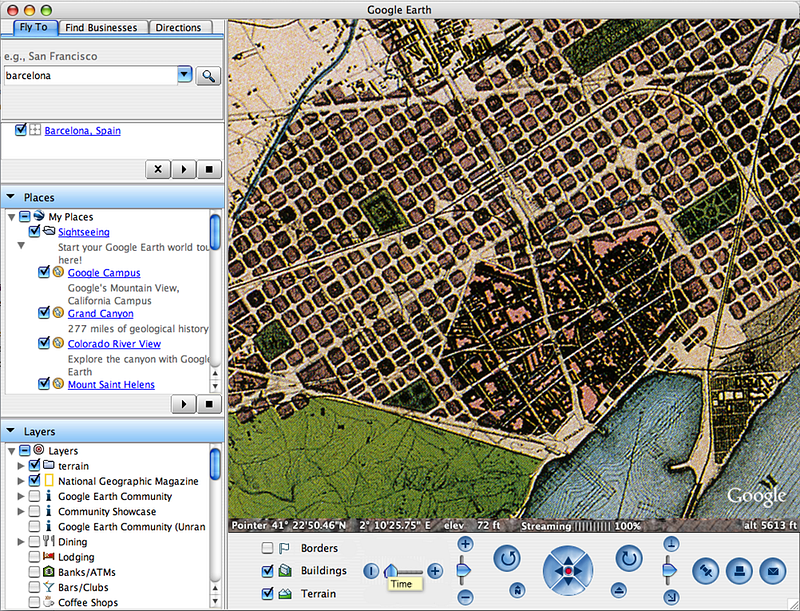

Whilst pawing Barcelona around — incidentally, what an awkward combination of movements Google Earth engenders? Grabbing, dragging, clawing, zooming, revolving, tilting. A haptic interface would seem more suitable to the object — I realised how well the application describes the form of the city. The beautiful, rigorous grid of the Eixample is clearly discernible, block after block interlocking neatly with those unique chamfered corners. At street level, the variegation in architecture and generous spacing disguises this economic, adaptable layout. In Google Earth, the traces of ancient city walls are perceptible too, a serrated edge separating the density of the Ciutat Vella from the Eixample.

My overwhelming sensation at this point was a desire to slide the city back through its development, to watch the port developments shrink back on to land, to see the Eixample retreat block by block, to watch the city walls rise up again … And then slide it forward. I’m still reading Joan Busquets’ ‘Barcelona: The Urban Evolution of a Compact City’ which is no doubt influencing my thinking.

I fabricated an image of a Google Earth application with an interface control for Time. I shifted things round a bit to make room for a horizontal slider control with which you’d be able to pull back the imagery through time. It would be possible to simulate satellite images for all of this, creating a smooth CGI morphed retreat of the city walls back to the original Roman settlement. However, I’ve used period maps instead. Whilst this creates a harsh disjunct as the differing styles of cartography clash, I prefer the texture this adds, a true sense of time conveyed by the worn maps, typographic development and varying material. From the 20th century’s rationalist monochrome accuracy via Cerda’s famous 1859 plan to the simplified, warped perspective of two maps from around 1706 drawn on vellum or canvas.

There is almost unlimited potential here — including overlaying different periods, annotations, a more suitable user interface etc. — but just in terms of conveying an idea, there’s a basic value in working within the confines of the current Google Earth interface too. Here’s a crude example, indicating maps of Barcelona morphing back from 2006 through 1970, 1930, 1859, 1854, 1740, and two from 1706.

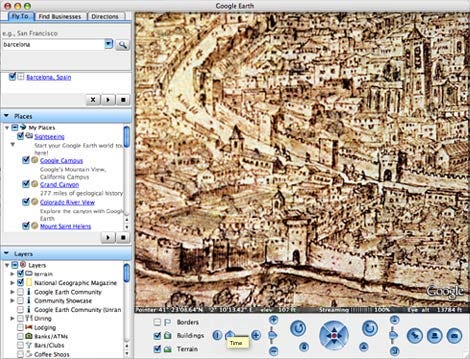

If we deployed Google Earth’s tilt control, we could even sneak in Wijngaerde’s drawing of the western sector of the city from 1563, showing the Rambla and Church of El Pi:

All maps are taken from Busquets or the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Historic Cities project.

The second extension that I’d like to see is actually one that wouldn’t be visible at all. After accumulating a few hours of virtual city stalking, it occurred to me that it’s all so quiet. 10000 feet up, one might expect not to hear anything. Closer to the ground, 70 feet up, we’d surely have a sense of the sound of the city? Imagine being able to turn on ‘sound’ and hear the sounds drifting up to meet us celestial listeners to Google Earth. There are numerous field recordings available — with plenty more to follow once location based services really kick off — with which we could augment the images with some richer representations of earth. I recently noted Metropolis Shanghai, which has brief sound excerpts such as ‘In the hustle of the Bubbling Well Road’. Could we hear this — and others — as we begin to zoom in to the Bubbling Well Road and set the time to 1938?

Again, in Barcelona recently, I quickly compiled the following list of representative sounds over a day or so: the gas man calling out to inhabitants of the Ciutat Vella; howling monkeys in the zoo pretending to be errant teenagers; a desperate woman, begging in Barceloneta, wailing a beautiful, desolate, ancient-sounding song; kids everywhere, all hours; skaters outside the MACBA; rubbish trucks outside our hotel on C/Argenteria a little too early in the morning; numerous church bells, drawing tides of people scurrying down the slender streets; the bewildering babble of Catalan; thumping Eurotechno in Seats failing to drown out the whine of circling scooters; a million hissing coffee machines; the sizzle of grills behind windows in ground-floor kitchens …

How vivid a representation of the city to hear these sounds; how interesting to hear the sounds change as you move around the city; and how about combining the sound feature with the ‘time slider’, as with the Bubbling Well Road sound above?

Google Earth, despite being the most fascinating application of recent months, is ultimately a somewhat dry, utilitarian device, as with Google itself. The fact it can generate coherent directions from A to B via major interstates is actually neither here nor there, ironically. And yet it inadvertently creates a near transcendental experience. Perhaps we should split the source code at this point, with one interface tending towards utility, and the other built for experience, expression and learning, started by adding a checkbox for sound and a slider for time.

This piece originally published at cityofsound.com on 29th January 2006, around six months after the mainstream release of Google Earth.

Leave a comment