An illustrated talk on the future of music, from 2005

Ed. This piece was originally published at cityofsound.com on January 4, 2006, based on a talk I gave in September 2005. I was working at the BBC at the time, and had been working with music ‘online’, as we used to call it, for about a decade by that point. I’ve tidied up images and links, but the talk is as it was, essentially—which means there are wild speculations and some utter irrelevances, but also a fairly accurate sense of what many of us were dealing with. Some questions raised here, whether shuffle culture might change song intros for instance, turned out to be accurate, whereas references to MySpace, cameraphones, and folksonomies are very much of their time, put it that way. Still, we were amidst podcasts and mp3 blogs, and enjoying the turmoil. From that distance, we couldn’t see iPhones and Android, Spotify or Apple Music, Roli Blocks or Teenage Engineering, and YouTube was a year old, but we could sense what was coming. My somewhat tiresome obsession over the minutiae of music metadata in the talk reflected my position at the BBC, as Head of Technology & Design, working through the architecture of our services for ‘discoverability’, whereas the broader questions of physical experience in a digital world—or rather, vice versa—would become a much deeper pursuit, with both objects and cities. Overall, though, whilst music has a very particular symbiotic relationship with technology, it also tends to reveal a deeper set of questions about culture and technology in general. Hence me re-posting this, almost 15 years later.

Below, the written-up and expanded notes for a talk I gave at a seminar called ‘The Future of Music’ at the Sibelius Academy, Helsinki in September 2005. The audience was music educators, music technologists, musicians, researchers and cultural policy makers. The talk built on my work at the BBC, but also attempted to describe an emerging terrain for the largely unfamiliar, and as such could work as a primer for aspects of this area in general — yet I also tried to make some points to move discussion in general along. Many thanks to Gustav Djupsjöbacka, Timo Cantell & Jonna Hurskainen of Sibelius Academy for inviting me.

Introduction

Oddly, for a session on the future of music, at a music university, I’m not going to play any music, nor talk about performance — because I aim to focus on things around music, on the experiential context around music and how that’s changing. I aim to highlight the huge opportunities being created around music at the moment, but also some of the implicit dangers of ill-conceived, careless or uninformed work in this field.

When it comes to their music projects, AOL have a slogan of ‘Discover, Experience, Own’. I’m discussing music experience in the first two forms, and both mainly in the popular, mainstream context — music discovery and music experience — although I will pick out issues and implications for classical and non-mainstream music. I’m not going to talk about ownership and commerce as such, though both are impacted hugely by these new approaches to experience.

Leaving aside the century-long evaporation of everyday music participation to be replaced by recorded phonography, it’s generally considered safe to argue that there is more music around than ever. We can look to the burgeoning digital music sector as well as the high street stores for evidence. For instance, the Yahoo Music Unlimited service provides access to over a million tracks for $4.99 per month. (As an aside, what is the value of each track in that? 0.0004c per track?).

And partly thanks to the iPod, there is more discussion than ever, an apparently increased focus on music. Yet I’ll argue that we shouldn’t mistake this discussion and focus for music being in good shape. For all the advances digital music affords, without some extensions to the way that digital music articulate music experiences, we could be in danger of diminishing music experience, and music itself.

Discovery

I want to initially focus a little on ‘music discovery’ — an umbrella term to describe a range of ways in which listeners find out about new music.

For instance journalism and music criticism, represented by the likes of Lester Bangs, Greil Marcus, Robert Christgau et al for music papers such as the NME and Rolling Stone, dominated music discussion for decades. On radio, DJs like John Peel filtered hundreds of releases from the music industry each week and provided an authoritative, critical voice for listeners eager to discover new tunes. These figures became seen almost as benevolent seers, helping to make and break thousands of musicians for a large, grateful mass audience.

Now this journalism is joined by thousands of new entrants, mimicing aspects of their functionality yet proliferating wildly in form, range and quality. Particularly the mp3 blogs phenomenon, in which we see some of the best writing about music online is coming from non-professional journalists, hardly amateurish about their research or presentation. Presented with sound samples, it’s a compelling new form of music journalism and wide open to newcomers. Podcasting, in which people record and upload radio-style ‘shows’ to the internet, is a newish activity closer to a DJ-style discovery service. There are aggregators of these new services, just as magazines and networks were earlier forms of aggregators.

In terms of authority, some of the entries about music at Wikipedia, a distributed ‘open’ encyclopaedia project, are extremely high quality; for instance these entries on Miles Davis or Porgy & Bess. Despite philosophical issues over this form of knowledge generation, when a Wikipedia entry gets it right, it can provide a valuable reference point. In essence, it provides a fascinating new model of knowledge generation in which ‘getting it right’ is a distributed, ongoing engagement with meaning; “the balance of knowing shifts to a social process”, as David Weinberger has it. For a cultural terrain as contested as music, it’s already providing fabulously rich detail, arcane and approachable in varying measure. It has the potential to rapidly outstrip previous encyclopedia projects, from Grove to Allmusic.com.

And it’s free. That is always difficult to compete with.

Recommendations and reviews form an important part of discovery, and here again we see a shift to distributed, fragment sources, aggregated together by services, sites and technology. We could look at sites like Metacritic, which aggregates reviews from elsewhere. In terms of recommendations within social circles, we could look at how music discussion chatters from one ‘instant messenger’ to another. Yahoo CEO Terry Semel (ex-head of Warner Bros, also indicating a shift of sorts) said recently:

“If you are an 18-year-old interested in film, you are not interested in what a 50 to 60-year-old critic thinks. You want to know what your buddy list thinks”.

Of course, ‘music recommendations from social circles’ are as old as the hills; what’s new is software’s ability to formalise, archive and communicate these recommendations, emanating outwards from tight social circles to wider and wider circles of discourse around music. In some senses, to enable a systemic socialisation of those recommendations themselves.

We could look at another areas, such as music photography. Aside from a few disposable camera snaps here and there, this was once a profession conducted by the likes of Mick Rock. Now, thanks to digital cameras, camera phones and interactive media built for sharing photos, photography in general is a daily activity for many, and music photography is conducted by fans; photography is distributed.

When a band is on tour, the photo-sharing site Flickr is awash with photos, uploaded contemporaneously e.g. Flickr aggregating all photos tagged with the words ‘bloc party’. It’s hardly the same as Mick Rock-style photography, and important to note that that practice continues too — this is additional activity, not displacement. It enriches music imagery by enabling new forms of photography and new communication of that photography.

In music A&R terms, we had ‘hitmakers’ and gurus like John Hammond (who ‘discovered’ Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, George Benson, Aretha Franklin and more) and Berry Gordy Jr., pictured below with his proteges, Diana Ross & The Supremes, Smokey Robinson etc.

Now we have discovery through distributed, software-based systems like peer-to-peer filesharing, which for some listeners enable a form of ‘taste test’ for new music, or the opportunity to expand their music collection for free. I’m not going to go deep into the numerous issues there. More importantly in terms of discovery perhaps, we’ll see later how truly distributed, networked systems designed specifically for music discovery — rather than acquisition — can work.

In terms of good old-fashioned acquisition we have, of course, seen an explosion of online retail opportunities around music, many of which have incorporated some of these distributed discovery features to aid recommendations for purchase. The undisputed leader is of course Amazon.com, whose innovative leadership in this area has created several of the core patterns users expect to follow around music, despite their early focus on books. These patterns include sound samples as a preview, album art, rating of albums, ability to leave comments, as well as the more complex ‘collaborative filtering’-style recommendations — “if you like this, you might also like this” — aggregated from millions of users’ buying patterns.

These patterns are now adopted by many of the smaller specialist shops, such as the excellent Boomkat for example, who deploy these techniques within a more characterful, music-orientated offering. Traditional ‘bricks-and-mortar’ high street record shops have adopted some of these tropes in response, as well as having their own sophisticated music discovery techniques.

[Aside: When trying to ascertain the internet’s efficacy in discovering new music, note how journalist Alexis Petridis sees possibilities only through the prism of things that ‘look like’ traditional journalism and discussion. Of course professional journalism still exists on the internet, not least at internet-only propositions like Pitchfork. But as the Arctic Monkeys story developed this year, traditional journalism has attempted to follow how the internet apparently broke the band through message boards and file sharing across social networks. Petridis et al often fail:

“The bleeding edge of the new-music revolution now feels perilously similar to the bleeding edge of a nervous breakdown. I turn my computer off and head for bed.”

The examples mentioned in this talk — mp3 blogs here, and later ‘social software’-based services — are generally very different models for discovery.]

So these broad shifts can, as in so many areas of culture, be crudely characterised as a movement away from ‘top-down’, single voice, broadcasted, edited, authoritarian models towards a more heterogenous, software-based, networked organisation of information, constructed in emergent fashion from a multiplicity of voices. It’s a crude over-simplification but not without merit. Music discovery is now an incredibly rich, complex terrain in which intelligence moves to the edges rather than the centre.

This movement could enable a richer, more beneficial model for music discovery, but only if the software and systems driving these discussions is carefully implemented — calibrated with specific knowledge of the subject area — in order to facilitate a richer experience around music. I’ll return to this theme and attempt to explain why, but only after exploring how the experience of music listening itself is changing.

Experience

Colourful portable music players

The idea that colourful, portable music players have heavily impacted upon the music listening experience in new and transformative ways needs to be tempered with a quick glance backwards.

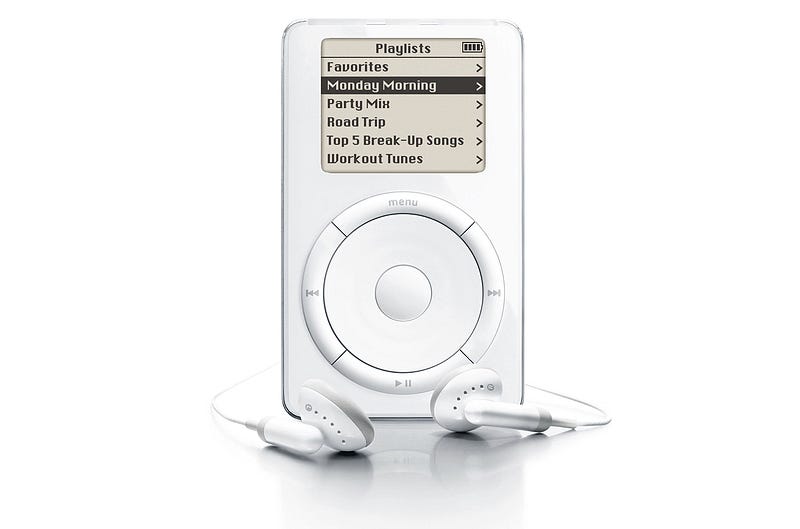

The iPod and its brethren can indeed be argued to have changed the music market to some degree — as I speak, music download sales are creeping upwards beyond the 5% region and has ‘rescued’ the singles chart in the UK — and it’s certainly had a huge cultural impact on the perception of the popular music experience.

But the idea that music products which are desirable through design, portable and crucially, personal, is nothing new as such. For instance my colleague John Ousby spotted the iPod’s similarity to the Regency TR-1, released in 1954 as one of the first small transistor radios, available in several different pastel colours and marketed with the incredibly contemporary-sounding mantra, “See It! Hear It! Get It!”. Importantly, it meant the newly emerging ‘teenagers’ could take their music out of the parentally-controlled living room too.

We can see a history of music going portable and personal from the 50s onwards, despite the impracticality of the vinyl medium to this form — even the highly implausible dashboard-mounted Chrysler “Highway HiFi”, through to the 60s’ portables the Tappo Kontakt and the record-destroying Vinyl Cutter of the ’80s, which were then joined by the ‘boombox’ cassette decks.

Now mp3 players continue this theme, but the biggest difference is one of wildly varying scale, with the device getting smaller and smaller while the amount of music it contains gets larger and larger. It’s now possible to carry more music around with you than people would have previously thought possible. Questions actually emerge of how much music we need to personally own, if indeed ownership is an important attribute of this experience. We could previously assume the average person’s music collection to be numbered in the tens of CDs, with music radio catering for a lot of (non-owned) music experience. Research on this ‘average everyday experience of music’ would be increasingly valuable, I feel.

Now, however, it’s possible to carry hours and hours of music in your pocket. If you have hours and hours. Napster’s recent research indicates that most digital music players are only just over half filled. Yet these new music services make it their job to immerse you in more music than ever — more than you could actually listen to — on devices which are increasingly small. Steve Jobs, Apple’s CEO and a consummate showman, makes a play of this whenever he announces a new iPod in front of the an audience at Apple Expos, pulling it from a different smaller pocket in his jeans each time. One wonders where he’ll have to pull the even smaller iPods of the future from.

So today’s devices for playing music embody a gigantic mismatch between the physical presence of music — previously embodied in physical containers — and the new digital presence of music — now invisible, without presence. This is a huge advance, albeit principally in terms of scale as with so many contemporary advances, but delivers a series of compromises which I’ll point out later, perhaps indicating that size isn’t everything.

Platforms

Leaving aside its device-based aspects, radio could be described as a platform or service for experiencing music. Again, we’ve seen huge shifts from the classic format of broadcast radio, forged by the likes of ‘Daddy-O’ Dewey Philips in the late-50s — the first DJ to play Elvis Presley — or Christopher Stone, John Peel, Alan Freed or Wolfman Jack.

Radio now can be a complex, interactive, time-shifted medium, increasingly in a call-and-response relationship with a network of listeners. (For some of the work of BBC Radio & Music Interactive in this area, you can hear a talk delivered by a few members of my team at the 2005 Emerging Technology conference here.)

Radio in the UK has been growing in range and popularity in recent years — the average Briton listens to an entire day’s worth of radio per week — and the growth of podcasted radio enables us to observe how the medium is changing across the world too, thriving as the professional radio industry is joined by legions of semi- and non-professional entrants (see Odeo.com for examples). But that’s another presentation for another day. For now, we can note that radio listening still accounts for a lot of music experience, but is also increasingly shifting into the kind of decentred, malleable, portable, personal forms described earlier.

Before we leave radio, it’s worth noting the radio-like music experiences prevalent in video games, a pursuit eating up leisure time. (Apparently, Nielson ratings in the States now record gaming as the 6th most popular ‘TV show’.) Bestselling games like Grand Theft Auto with its in-car radio stations, and the sports franchises created by Electronic Arts both feature music as an integral part of the experience. Steve Schurr of Electronic Arts (EA) notes: “I left the record industry to get into the music business … Games will be the new radio, the new MTV and the new music store all in one”.

EA’s own research finds that 55% of gamers had learned about a new music artist through a game, with 33% subsequently buying a CD by that artist. The band Good Charlotte saw their sales of 300,000 albums increase tenfold after being featured in the EA NFL game Madden. Green Day’s “American Idiot” debuted on Madden NFL 2005, weeks before the single hit radio or MTV; the album of the same name went on to be one of the most successful records of 2004, winning the Grammy for Best Rock Album.

This is a new platform for music experience, featuring some of the ‘backgrounded’ characteristics of broadcast radio and film soundtracks, but within the heightened immersive environment of an interactive game, enabling serendipitous discovery too.

Contextual ‘carriers’

Having looked at devices and platforms, we should focus on the ‘carriers’ of the music itself, or their near equivalents, in order to figure out where the context around specific pieces of music is represented, or otherwise emerges.

Note: When giving a speech, I carefully place this following section by showing a lovely but defunct pianola roll, to illustrate a history of music technology changing the form of music — with advances sometimes eradicating previous forms of playback technology, generally for the better, despite the endlessly alluring, purely nostalgic charm of old technology.

As Evan Eisenberg has it:

“The progression from piano to pianola to phonograph may appear degenerative. Yet all three are machines … In one sense, the pianola is more mechanical than the phonograph, certainly than the electric phonograph; it is more machine-like, more rigid and insensitive to nuance. In another sense, though, an instrument is mechanical to the degree that it performs musically important tasks for the player. The guitar takes care of intonation for you. The piano takes care of intonation and (to a degree) timbre. The Hammond organ takes care of intonation, timbre and chording. The phonograph takes care of everything.” [The Recording Angel by Evan Eisenberg, p.145]

This kind of perspective is fundamental in separating nostalgia from a more cold-eyed assessment of technological progress entwined within music experience. This, in order to assess the ways in which technology has always affected the form of music, whether that’s the technology of the violin that emerged from Cremona at the beginning of the sixteenth century, or through the pianoforte, pianola, listening booth, phonograph, the electric guitar, cassette decks, MTV and so on. I also deployed my pianola roll given its similarity to early computer programming systems. More images here.

From the late-1930s, recorded phonography was generally experienced within close proximity to something known as the record sleeve. For half a century, listeners had to effectively ‘move through’ the vinyl’s cardboard sleeve, traversing an increasingly rich experience of representational and abstract photography, surrounded expressive liner notes … and what we’d now call metadata.

[Ed. In the presentation, I present the cover of Miles Davis In A Silent Way as a typical example of a late-60s album, rich in contextual information, from photography and typography through to professionally-written poetic liner notes, as well as details of the band, the producer and the recording environment.]

I also showed a few physical artifacts, such as Marvin Gaye’s Trouble Man sleeve, featuring the additional fold-up flap built into the sleeve, apparently merely to accommodate Marvin’s fine flares and shoes. I also showed John Coltrane’s Ascension, as another classic of its kind, and John Cage and Letajen Hiller’s album HPSCHD, which featured a computer print-out as part of the package, containing instructions as to how to ‘play’ your volume controls whilst listening to/performing the piece. These to illustrate the flexibility and creativity implicit in a physical representation of music. One could show a thousand different varying examples here …]

With the advent of compact discs, designers and musicians quailed at first in response to the lack of physical size and flexibility afforded by this new format — note the size of the In A Silent Way boxset against the 12″ vinyl equivalent.

And yet, designers eventually found ways to create rich physical, visual contextual experiences around CDs. We can look at the work of the lavish boxsets created by the major labels — for example, In A Silent Way by Sony — or created by smaller, avant-garde labels, such as Tzadik, Rune Grammofon, Winter & Winter, Hat Hut, Screwgun, Revenant et al.

`Strange hybrids emerge, such as the ‘Vinyl Classics’ range of compact discs, currently on sale (e.g. Johnny Cash Live At San Quentin).

Rather more subtly, the replica vinyl compact discs on sale in Japan (e.g. here, Miles Davis Kind of Blue) featuring original liner notes and all.

Eventually, the compact disc sees an essential diminution of visual real estate, but creates new physical artifacts to contain and express contextual information around music.

Similarly, the practice of mix tapes generates highly personal ‘contextual carriers’ for music. The metadata here is patchy (the practice is far older than the word ‘metadata’) but the personality of the mix tape can be incredibly powerful, featuring at least the handwritten notes from a friend, and at best a visually rampant feast of cut’n’mix collage. These are represented well in Thurston Moore’s book Mix tape: The Art of Cassette Culture and Xavier Carbonell, Joaquín Gáñez and Garikoitz Fraga’s superb compendium Gracias por la musica, which contains 700 homemade CD and cassette covers, sometimes containing more interesting graphic design than professional versions, and always conveying highly personal meaning

.Today, a contemporary equivalent might be the mp3 playlist, meaning that sharing of music remains popular, but Moore notes a difference. In compiling his book “(a)lmost every person bemoaned the fact that their beloved tapes had vanished. So many people had talked about the beautiful and wild cassette cover art adorning their tapes …”. Moore adds that he never did that, though. For him, “it was the simple listing of artists and the song titles which held the magic”.

Aside from the listing, easily enabled in today’s music sharing applications, how much did the augmented hand-written notes add? With scrawled and photocopied artwork, or a letter alongside, how much more evocative is the context around the music? Moore suggests that iTunes playlists are becoming the “Hallmark of mix tapes — all you gotta do is sign your name to personalize it”. But are you really personalising by digitally signing your name?

Whilst a future digital identity might well be richly evocative, the current implementations are vapid to say the least. And while the personal curation of music will always be valuable when received, what are we losing by removing personality? What disappears when the physical wrappers around music fade away? Are the tracks alone enough?

We could argue that much of that contextual information — and more — is now available online. Indeed, much of it is, on encyclopedic sites such as those mentioned previously, and on lavish artist sites and loving fan sites (pictured here a site for the musician Sufjan Stevens — a typical artist site, containing much contextual information for fans to pore over.)

The iTunes environment is generally visually rather staid, as we’ll see, but when Apple decide to create a Music Store Exclusive — pictured, for Kanye West — we get an expressive, informational environment around the artist (albeit with text often licensed from sites like Allmusic.com). Music video becomes a new visual accompaniment, and now also part of the iTunes/iPod experience — yet contains little or no factual or personal metadata

.However, these experiences are not part of the music listening experience — the artist website and digital music stores are both unconnected to the music experience (despite the apparently close integration within iTunes).

With albums, the listener would hold the sleeve in one hand and place the needle on the record with the other. The same with cassettes, mix tapes or otherwise, and compact discs. You had to parse the contextual information to some degree, even absent-mindedly, to get at the music. Here and now, the context has floated away from the listening experience. A listener might google for more information around an artist while listening, but this is surely an ‘edge case’. Again, more research on listening behaviour would be fascinating.

Physical experience

So the physical experience is shifting quite radically. As I noted, the handling of the record sleeve was part of the experience, meaning a short journey, however subconsciously, through context to content. As the context has melted into air — as the music has ‘become’ digital; with music experiences embodied as mp3 players — some components of meaning in music have been detached from experience.

Playing a record is a powerful physical experience, the very act of dropping needle into groove evocative, rewarding, embodied. The ‘user interface’ of the vinyl record and record player is flexible, intuitive, usable, useful and emotive. But it seems both anachronistic and nostalgic to even pause to mention this in the context of thousands of songs in your pocket. The visuals I chose to illustrate this section are screengrabs from the US TV show ‘Lost’, in which the camera lovingly pores over an unnamed character putting on a record, zooming in on the deck’s cartridge on vinyl, music filling his 1970s subterranean pad. This is ‘playing vinyl as signifier of another time’; indicating an experience frozen in history.

So the physical experience of vinyl (and its related media) afforded a close connection of music context and music experience. The record player delivered a user interface which was both flexible and expressive, and crucially meant a direct engagement with contextual information explicit and implicit. Explicitly, sleeves were constructed to carry vast swathes of information around the music; implicitly, the grooves in the record conveyed information about the length of track, the number of tracks per side and so on, even the sound itself if you were obsessive enough. The needle-drop method of previewing music — bumping the needle across the record from track to track, or within sections of a piece — provided real control over sampling the music contained therein.

Comparatively, with today’s music experience environment, we see a shift away from the music towards devices and services. In iTunes, there are only expressive visuals in the context of a ‘sell’. With the iPod Shuffle, there is no visual at all, no screen to display any contextual information whatsoever. Whilst it’s a fascinating, useful device, in terms of conveying context, knowledge, learning or the most basic information about what one is listening to, it has nothing to offer. Witness the marketing around the iPods and we can see that visual seduction is now at the device level, not with the music. The design of the device is what people covet, rather than the design around music itself.

And yet mp3 players are not particularly musical devices, intrinsically. There is nothing of single-mindedness of the record deck about them. As devices, they can handle your address book, photos and diary with equal facility as your music. They’re essentially a hard disk — or flash disk — with a physical interface. Are they, in essence, musical? With the convergence predicted (or not) around mobile phones, products like the Nokia N91 and Motorola ROKR are also seen as music devices. They too follow some of the design patterns set by the dominant mp3 players, whilst being first and foremost mobile phones and adopting their key characteristics accordingly … so just how ‘musical’ are they?

However, these devices and others have enabled a incredible reduction in the physical space required to store music, and a vast increase in the amount of music one can carry around. It’s clearly a compromise. Many will want to reduce the storage space music used to require, and in this sense, there’s a displacement involved in the physical accoutrements of music disappearing into transient experience.

Overall, we can note an increasing separation of context from experience, via either a diminution or complete absence of a physical interaction or visual and textual information around music.

But if we’re seeing a shift away from traditional music experience hardware, and the physical artifacts around music, we’re also seeing a shift towards a new kind of contextual music experience; an experience which is software-based and increasingly social. It’s worth focusing on two exemplars of what has been known as ‘social software’ around music, in order to illustrate what the new digital music experiences have to offer.

New Musical Experience: Two quick case studies

Last FM

First up, Last FM, a bit of social software based entirely around the experience of music, in both personal and radio-like contexts. A light software plug-in, called Audioscrobbler, sits in the background of your listening experience on a computer, such that as you play CDs, mp3s or other digital music, it tracks what music you’re listening to and records that on your personal ‘space’ at the Last FM website.

By aggregating these listening habits across many thousands of users, Last FM is not only able to offer accurate, useful recommendations to enable you to discover new music but also provide highly personalised streaming radio services. Effectively, by learning from observing every bit of music you play digitally, it can offer a highly-tailored series of discovery services around music. It’s quite brilliant, as far as it goes.

Let’s take a quick walk-through some of Last FM’s features, via their record of my own personal listening habits (currently, it’s noted over 25000 tracks I’ve played via iTunes or my iPod) (Ed. Years later, and still active and linked via services like Spotify, it’s over 90,000 tracks); charts of my listening habits over time, organised by artist or track; what those with similar taste to me are listening to; what my friends, of those also on Last FM, are also listening to; album pages indicating who’s listening to that album and how popular its various tracks are; artist pages, with automatically generated ‘similar artists’ purely drawn from correlating listening habits i.e. no prior knowledge at all; and finally custom radio stations based around metadata (in the form of ‘tags’) that users have added around music, or based on an artist you like, which then plays you tracks by that artist and then artists similar to that artist, again based purely on what the system has ‘learnt’ by aggregating patterns of listening.

No software intrinsically knows that Keith Jarrett is influenced by Bill Evans in some way — yet Last FM can infer a relationship by noting that people who listen to lots of Keith Jarrett quite often listen to Bill Evans too. By this simple relationship — similar to Amazon’s collaborative filtering model — Last FM can help build a genuinely useful world of what appears to be knowledge around music. Or at least information about connections. We’ve never had such a public, accessible depth of data about listening habits in such a bewilderingly complex level of detail before.

Problems emerge, essentially based around metadata and a purely systems-based model of knowledge generation, but as a user it provides a fascinating and useful ‘presentation of self’, and by modelling the subtle differences between your friends’ listening habits and those of people with the same musical tastes as you, it provides an excellent example of the power of network effects in applied social software. These systems — which in the widest sense comprise the blogs and photo-sharing sites mentioned earlier — are increasingly ripe for acquisition by the existing content industry. Witness News Corp’s investment in MySpace, predicated partly on the discussion of music therein. As discovery and experience platforms around music, we can’t ignore them.

Pandora

Pandora also aims to provide a music discovery platform, again based on delivering music recommendations and providing a streaming radio-like experience, but is constructed in a quite different way to Last FM. Where Last FM infers information about connections in music by examining patterns of usage having combined vast quantities of listening data, Pandora uses connections which have been ‘authored’ by panels of experts.

Deploying an in-depth analysis of the intrinsic formal qualities of music itself — in terms of tonal quality, colour, rhythm, timbre, composition, instrumentation etc. — Pandora uses a few simple introductory questions about favourite artists, from which the system offers the user some tentative suggestions of pieces from a vast database of music, almost as if in conversation, which the user can then accept or reject, delivering a little more information back to the system. Pandora learns from this, and suggests more music, all the time building a picture of the kind of music the user appears to like, again by analysing the components of that music and connecting it to music in it’s database with shared or closely related components.

It’s a powerful system based around expert knowledge and appears to deliver very high quality recommendations quite rapidly. However, issues remain here too. One, in terms of scalability, as the ‘Music Genome Project’ underpinning Pandora requires panels of experts to analyse and capture music — apparently “15–30 minutes (of analysis) spent on each composition capturing the hundreds of musical nuances that give each song its unique sound”.

Where Last FM will continue to thrive and perform better as a recommendation system the more music metadata that’s thrown at it, Pandora only ever has a subset of available music to recommend, based on how many times the experts can perform that half hour of analysis per day. Despite the pronouncements about scale earlier, this may be a seriously limiting factor. Secondly, by appearing conversational in form but limiting the user’s input to ‘thumbs up/thumbs down’ interaction, it feels, in the words of a friend, a curiously “bloodless” experience. Compared to the complex interactions of, say, record shop staff as caricatured in Hornby’s High Fidelity, or discussion with a trusted friend, there’s little personality there.

It too relies on quality metadata, and there are several issues with the system as it stands. For instance, in my demo, taking the input “Sufjan Stevens” and then checking whether I meant “Sufjan Stevens, Shakin Stevens, or Cat Stevens?”. Can you imagine a record shop attendant doing that? Still, these elements are relatively easy to solve.

The overall model of Pandora is a fascinating alternative to Last FM, relying as it does on studied, human expert knowledge rather than software-based inferred connections. It appears to work very well at providing recommendations, which is the stated aim, though Last FM appears to be the more engaging experience and more scalable system. I suspect that welding the two approaches together into one coherent experience would deliver a very powerful system indeed.

Impact on the form of music itself

I’m aware that earlier sections of this talk might sound a bit ‘nostalgia ain’t what it used to be’, but as noted earlier, technology has always changed the form of music but generally by expanding its repertoire.

For example, electric amplification partly creates the conditions for rock music; samplers partly create the conditions for the dance music. But focusing on these new digital music experiences, in which I’ve argued that the playback medium is becoming increasingly disengaged from the contextual experience around music, I’ll now discuss how that context might also begin to fade away completely.

iTunes, Last FM, Pandora and everything else mentioned thus far are still niche activities in comparison to the mainstream music experience, but there’s little doubt that digital music listening is growing in both volume and cultural significance. Given this trajectory, and that diminution or demotion of context, this new technology could be harmful to the form itself, rather than enriching it. This may often be inadvertent, based around lack of knowledge, care, or long-term view, but is a problem either way.

The effect of metadata

Given that many of these systems rely on accurate metadata, aka contextual information around music, it’s surprising how little flexibility or accuracy or general importance is attributed to metadata itself. This is a particularly acute problem for those genres, often non-mainstream, in which contextual information is most vital and most detailed.

The best example of this is explored most thoroughly by Wayne Bremser’s brilliant essay at harlem.org, in which he illustrates the paucity of metadata in an average mp3 file, or the iTunes application in which it is experienced, as compared to the average vinyl jazz album of the mid-20th century. It’s difficult to conceive of how these new music experiences can be an advance when we see iTunes conveying that the track ‘Jeru’ is by Miles Davis and it’s off the album Birth of the Cool … and that’s it. The genre may or may not be there, and may or may not be at all useful — on another piece, it could be ‘World’ for instance, which is particularly unhelpful; ‘Jazz’ will be applied equally to Kenny G and Derek Bailey, despite the obvious chasm.

The date field in digital music services is frequently incorrect, generally based around the year the CD was last re-released rather than when the music was recorded. On the record inlay alone, we learn the names of all the players in the band and what they played; who composed it; and if the genre is there, what particular sub-genre of jazz it is associated with; which label it’s on; with further implicit information conveyed by the graphic design. On the sleeve, as noted previously, one would learn where it was recorded, who the producer was, as well liner notes and cover art etc. In a music like jazz, or classical, folk, blues, avant-garde — essentially most non-mainstream music — this contextual information provides an architecture of knowledge upon which listeners can discover new music. It’s relevant who the bass player is. It’s relevant who produced it. It’s relevant where it was recorded, when it was recorded, on which label. There are numerous facets around information architecture for music — some noted here. The average mp3 — which is limited in its ID3 fields to artist, track, album name — has none of this information.

This applies to varying degrees across most music genres and is particularly acute with classical music, where such facets are especially relevant — such as the composer, conductor, principle soloist, ensemble, possible even instrumentation in the case of ‘Early Music’. Digital music services are slowly eroding this sense of detail from contextual information around music.

There is only one place to store ‘artist’ information in an mp3 file. So in this sense, is Glenn Gould or JS Bach ‘the artist’ when it comes to the Goldberg Variations? Both are, in a sense, but digital music platforms don’t make this most basic level of complexity part of the experience. If one digs deeper in iTunes, Bach can be stored as ‘Composer’, but the software has little serious support for this information, and Apple would appear to have little serious intention in enabling it.

Steve Jobs describes the core “DNA within Apple” as “taking state-of-the-art technology and making it easy for people” (The Guardian, 22.09.05). This is often A Good Thing from a product design perspective, but as products become generators for actual social connection and cultural meaning — for symbolic performance — when does this become over-simplifying?

[Aside: I’m often focusing on iTunes as it’s generally perceived as ‘best of breed’ in this field. And I agree with that assessment. For all its flaws and shortcomings, it’s a generally well-designed and hugely successful software product. Another best of breed, Amazon, quite often has shocking metadata, with highly variable artist names and titles, and music randomly dispersed between their two main search-areas, ‘classical music’ and ‘popular music’. Sometimes this isn’t problematic, but beyond usability, software services such as these increasingly possess hegemonic influence, hence the focus and critique.]

Further problems emerge when systems which do use metadata are insufficiently aware of the cultural field in which the system operates. For instance Last FM, despite its obvious computational brilliance and careful thinking about social patterns, struggles with the following example perhaps due to the blunt application of a systems-led view of the field on to something inherently, humanly unpredictable.

The title of the Sufjan Stevens album based around the state of Illinois can be listed as ‘Illinois’ or ‘Illinoise’ or (for Slade fans) ‘Come on feel the Illinoise’. That’s the first problem. Last FM can only really handle one title, and while it does this pretty well, that doesn’t match the actually appealing ambiguity over the album name that, say, an experience like walking into a record shop and asking for “the Illinois album” could handle rather more elegantly. Still, Last FM handles it well.

However, the second track on whatever the Illinois album is actually called, has the title ‘The Black Hawk War, Or, How To Demolish An Entire Civilization And’. Or at least that’s how it appears in my listening profile. Hovering over the name indicates that Last FM actually thinks it’s called ‘The Black Hawk War, Or, How To Demolish An Entire Civilization And Still Feel Good About Yourself In The Morning, Or, We Apologize For The Inconvenience But You’re Going To Have To Leave Now, or, “I have fought The Big Knives and wil continue to fight the’ (sic).

And yet clicking on that track reveals two things. Firstly, that Last FM’s visual design struggles to convey a track name that long — it clearly wasn’t designed flexibly enough to handle the fact that an artist might want to name their track in such a way. Secondly, and more importantly, it reveals that zero people have listened to that track. That couldn’t be right, so I clicked on the album page listed below, and then on the second track from ‘their’ listing. This revealed that Last FM thinks the second track on whatever the Illinois album is called actually has the title ‘The Black Hawk War, Or, How To Demolish An Entire Civilization And Still Feel Good About Yourself In The Morning, Or, We Apologize For The Inconvenience But You’re Going To Have To Leave Now, or, “I Have Fought The Big Knives And Wil Continue To …’. Spot the difference. This version of the trackname had been listened to by many more people.

This isn’t exactly a crime against music at this point, but if we assume that systems like this will increasingly be ways in which people discover new music, this kind of accidental metadata anomaly means that this track is simply less likely to be discovered. All because the artist chose to give it a ludicrously long name. That is, I’d suggest, his prerogative and a system which is designed around an in-depth study of this cultural field would cater for this.

The length of this particular filename is a very real problem if you have an iPod Shuffle. In this situation, the file won’t actually copy on to the device, apparently due to the length of the filename being too long. This is a situation in which each component is effectively controlled by Apple — and it still breaks. This results in this track being listened to less frequently. (Rename the file ‘The Black Hawk War’ and it works.) Again, the technology choices around metadata are here limiting the music experience.

Metadata systems have to be carefully articulated in order to deal with a cultural space as complex as music. For instance, there are two artists with the name ‘Donna Summer’. Again, record shop staff could probably help you, but can our new music systems? Last FM probably could, but not many others.

The near-infinite diversity of music requires a fair amount of attention on localisation, as the following variants on Shostakovitch’s surname reveal that Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович (correct Russian spelling) = Dmitriy Shostakovich (English transliteration) = Dmitrij Schostakowitsch (German transliteration) = Dimitri Shostakovich (alternative English spelling of the first name). There are more variants, and most music metadata systems currently don’t help at all. At a basic level, even a sophisticated entrant like Last FM thinks there’s a difference between Paul Schütze and Paul Schutze.

Knowledgeable humans can easily pick out the connection between Bob Marley, Bob Marley and the Wailers, and The Wailers. Or that The KLF, The Timelords and The JAMS are separate projects but tenuously linked together too.

We’re comfortable with the ambiguity and unpredictability with which the Afro Celt Sound System become the Afro Celts, or the band Love and Rockets release an EP under the name The Bubblemen. Or that Aphex Twin and Polygon Window are the same artist. Legal reasons led to Dan Snaith, who released albums under the name Manitoba, changing his name to Caribou. Systems struggle to deal with complexity like this, unless the complexity is in-built and highly situated. Last FM’s observation-based approach would spot many connections here, but not all, and few systems have Last FM’s scalability. Its complexity means that it will struggle to become mainstream too. Do we have to do this trade-off between complexity and simplicity? Is that good enough?

What’s the connection between Ransome Kuti and Fela Anikulapo Kuti? Between Howe Gelb and Giant Sand? Between Slim Shady and Eminem? Fans know. A good record shop owner would know. A good DJ would know.

Then there are misspellings and variations e.g. Guns and Roses for Guns ’n’ Roses. iTunes has no conception that Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy is related to Will Oldham (they are essentially one and the same). In fact, it doesn’t even know he’s related to Bonnie “Prince” Billy (note the inverted commas). Or that Magnolia Electric Co. is the same as Magnolia Electric Company. Or the soundtrack to “A Clockwork Orange”, which was released with the composer of several tracks listed as Walter Carlos. Years later, Walter had a sex change and became Wendy. How do we join them back up, as it were? What about the difficulties over the titles and progeny of remixes? Or the tilde used as punctuation in Japanese subtitles?

As if to cap it all, there is an artist called Various Artists. (Ed. And almost impossible to find now, and link to.)

These are solvable, given engagement between those that know about music in particular and those that know about information in general. But they’re not being solved.

Visual meaning

In potentially less destructive fashion, the visual and symbolic impact of the track name is lessened hugely when viewed in any digital music application.

Below, viewed in iTunes, the track name scrolls past a narrow window for the track name. The visual design is a clear compromise, based around an average shorter track name. Compare to the way the track name can be displayed on the back of the compact disc, with ample room for the name to roam around and with the typeface conveying further cultural meaning.

All track names in iTunes are conveyed in the typeface of iTunes, which in a sense obliterates further implicit context around the track. These examples are from iTunes, but would apply across most if not all digital music applications. By converting track names to digital information, they become malleable within digital spaces — a huge advance — but here at the expense of any meaning in typography and graphic design. That may not matter as much in a spreadsheet, but it should matter more when representing art.

Cover art is irrevocably stunted across these new experiences — as illustrated below, the shift down in gears from the 12″ sleeve to the compact disk boxset to the cover art as it appears (roughly, generously) in a typical digital music service, when it appears there at all.

Much of the time the cover art just isn’t present. All the physical impact is about the device, as illustrated in the seductive marketing around these devices. This again illustrates that the contextual information around music is considered less important.

Interoperability

Many of these music experiences offer limited catalogues too, based as they are around a series of deals with content owners. When I gave the presentation, Last FM had not heard of the Johnny Cash album, Live At San Quentin. It’s since been added to their database, indicating the scalability in their system. However, move across the major players in this area — Napster, Rhapsody, iTunes and Yahoo Music Unlimited, say — and you’ll find varying catalogues based on particular business deals. For instance, records on the ECM label are not available in iTunes Music Store. (Ed. They weren’t at the time; and it would take a decade or so for them to appear on Spotify.) Compared to music retail on the high street, who could order you more or less any record they didn’t already have in stock, this also doesn’t seem like an advance.

Further interoperability issues emerge in terms of format, which is increasingly tied up in a chain with a retailer and a playback device. Again, the history of music playback technology reveals format after format being replaced — from wax cylinder to shellac to vinyl to cassette to compact disc to DAT to minidisc and so on. But what is different now is the pace with which formats are being replaced.

Thurston Moore noted this about the mp3 format:

“But even if MP3 music sounds lame, as long as it’s recognizable in form, free, and shareable, it’s here to stay.” [Mix Tape]

But mp3 itself may not be here to stay at all, nor will AAC, WMA, Ogg etc. Not in the sense previous formats were. Replacement is increasing in pace. Interoperability is reducing. Microsoft’s attempts to put the listener’s mind at rest in this bewildering blizzard of choice. But as Oren Sreebny notes, will ‘Plays for Sure’ be playable for sure in 100 years time? It seems unlikely even within a decade. Previously, you were free to buy music from a retailer and know that it would play on your entirely independent device. Buy a record in any shop, it would play on any record deck. Now the digital music retailer locks you in to a particular format: Apple to AAC, Real’s Rhapsody to Windows Media, and so on. This does enable new business models for the music industry, but in real terms the consumer appears to get a diminished choice as a result.

At the BBC’s Information & Archives unit they are machines made to order, for playing back everything from wax cylinders and shellac onwards; a room devoted to devices for dealing with ‘obsolete formats’. Each format had a good few decades of adoption before fading away, but it’s going to be increasingly difficult to ensure all these digital formats will be playable in future, to keep a track of the digital rights management software required to unlock the music.

Shuffle culture

I’ve written previously about some of the meaning in ‘shuffle culture’, and the fascinating space it inhabits, now being appropriated by all sorts of formats and media cf. the Jack FM radio format. It feels part of a newer, wider cultural form, the compelling factor being the contiguous, overlapping collision of the overall mix, rather than the discrete pieces of music themselves.

But there are dangers of a stunted experience here too, as 30-second sound samples become a de facto way of sampling music in digital music stores, but with none of the flexibility and instinctive control a needle on a record has. mp3 players may tend towards people skipping tracks more, given the easy facility for doing so — again, this is pure conjecture and requires research, but anecdotally there would seem to be some evidence that people skip more and listen to full or longer tracks less.

So will musicians craft introductions to songs to be instant hooks? Will everything have to be as instantly recognisable as Stevie Wonder’s ‘Superstition’ or Frank Zappa’s ‘Peaches En Regalia’?! What about the more unrepresentative introductions? The oblique patterns that Bill Evans and Paul Chambers describe as the introduction to Miles Davis’s ‘So What’ give little sense of what’s about to follow. Do we want an attenuated attention span impinging on music creation so much?

(Ed. It turned out this issue was one I was right to highlight, as music became focused on gaining the crucial 30 second listen on Spotify.)

Elsewhere, the shuffle experience can be as aurally destructive as it is creative — what about mixes or live albums which are intended to segue from one track to another without the second-long silent lurch the iPod interjects?

On balance though, the shuffle mode would seem to be generally positive, formally, or at least only potentially restrictive. I’ve listed many other advantages of these new music experiences too — in terms of the increased volume of music they enable, in increasingly small physical spaces; in terms of the shared, social aspect around music; in terms of malleability of digital information; in terms of new listening experiences like shuffling, and so on — but this appears to be at the cost, at the moment anyway, of some fairly basic and important contextual information, from additional metadata necessary for constructing knowledge through to visual meaning.

The possibilities afforded by what we called “social software” are enormous. And yet the richness we’re losing would look to be equally enormous. Slide Pandora or Last FM alongside the vibrancy and personality of the “contextual carriers” I showed earlier, and they suffers in comparison. Pandora is as bereft of people and emotion as a bad architectural drawing. Last FM fares better, by integrating friends and neighbours into the environment, but hardly compares to the physicality and personality of previous music experiences. Whilst we gain much from building digital systems, it might appear to be at the expense of complexity and flexibility. Unless …

My intention with this presentation is to highlight this compromise, and ask whether it’s one we’re willing to make? My answer is that we have a choice about how we implement these systems, and that we should be careful to do so in such a way which retains the advantages of these new music experiences whilst retaining the best facets of previous ones.

Recommendations

Some of the negative aspects of the new music experiences mentioned above might seem minor, nitpicking even, particularly in the context of the all-too-easy nostalgic view of an earlier age. There really does seem to be more music available to the consumer than ever before. This is surely a good thing. But how much music can one discover, experience and how much does it actually mean without context?

Services like Last FM, Pandora and iTunes all rely on systems which function to optimum when given highly accurate data. Compared to fuzzier, conversational matching of previous expert systems — aka music mavens, record shops, good journalists and DJs — it’s potentially restrictive. Unless music itself engages.

It’s been suggested that the most important, innovative companies in music are now Apple, Yahoo, Microsoft et al. These organisations create significant elements of the contemporary music experience, and the music world — not just the record industry — needs to engage with the nuts and bolts currently being forged by these new players. Equally, the music world will need to integrate with and partly populate the smaller players Last FM, Musicbrainz and Pandora. At this moment, this last area is likely to be most open to co-creation and yet the former industrial giants is where the mainstream experience is.

Recommendation: Employ a multidisciplinary design processes

I’ve previously recommended the importance of ethnographic user research in order to construct rich models of cultural fields, as part of the product design process, and that will help. Another way of achieving these rich models is for those in the traditional music infrastructure — educators, policy makers, music technologists, musicians, researchers, label owners, promoters, designers, editors, open-minded industry folk — to engage directly with those constructing these systems. (The recent appointment of Bill Buxton at Microsoft is a promising move).

The systems are then informed by the symbiotic process of the designers also being users. From a software perspective, this would be called writing ‘situated software’ or the typically charmless ‘eating your own dog food’. Without this connection with context, simplicity is foregrounded at the expense of a musical experience which is genuinely variegated.

All of this is best enabled by a multidisciplinary approach, in which systems-led thinking is balanced by deep insight from music expertise and ethnographic research. As discovery and experience becomes more distributed, more curatorial — in a sense, less about traditional music industry A&R — the decisions that programmers make are now as important as those that Lester Bangs, Berry Gordy Jr and John Peel made.

We may also need to think about pulling the curriculum apart and start joining together these schools of thought — much as John Kieffer has noted in the context of business skills. We can fuse the technology and software side together with the knowledge and agency of the audience and bind this to those who understand the cultural importance of music and what music is. In this way, we can create systems which combine the best advances of the social software movement infused with centuries of music knowledge, just as previous generations of music technology improvements were informed by this.

Pandora illustrates an approach which garners powerful music recommendations from deploying music expertise, yet it doesn’t have the scalability or truly distributed model of Last FM. But Last FM in turn has metadata issues, too much immediate complexity for the mainstream user and a diminished physical, visual experience common to all digital music services.

Recommendation: Rich metadata to provide rich context

On the metadata side, we could look to the fine model of the open source, “community music metadatabase” project, Musicbrainz (which underpins aspects of Last FM, amongst other things). Most of the examples of metadata anomalies described above — from Shostakovitch to Fela Kuti — were plucked from lurking on the Musicbrainz developers’ mailing list. With their concept of ‘advanced relationships’ we have one of the few metadata systems capable of indicating the rich complexity implicit in music. Talk to some digital music services and they find fields for composer, conductor, ensemble, principle soloist all a little taxing. It’s simply too complex for the average user, and therefore it doesn’t get modelled.

Fair enough, if the bottom line is the driver. But is that a rich enough view for an increasingly powerful hegemony around music? Musicbrainz provides a scalable, detailed foundation for a contextual framework around music.

What Musicbrainz needs are interfaces for products constructed on top of that foundation which can develop from simplicity to complexity at the pace of the user, which create a richer view of this metadata and expose it usefully within the music experience — if we don’t see it, we don’t care. Only by balancing interfaces which expose the architecture of music in useful ways will induce listeners to look after metadata. If we can create visual or physical information-rich products which expose metadata in genuinely useful ways, almost as a side-effect of music experience, then this metadata foundation becomes rich, deep and well-constructed.

Lest this metadata seems all a bit academic or mechanical, a primary purpose should be to enable real character to emerge around music again. This would be an extension beyond even Musicbrainz to ensure that passionate discussion for music — no matter how apparently ephemeral — can be captured and utilised as part of a music experience. Last FM has the facility to integrate blog-like posting, groups and discussion around music, which is promising, but doesn’t come close to the character seen in myspace (see addendum on myspace) or LiveJournal. This aspect of context is a good candidate for further ethnographic research.

[Aside: Useful metadata can also garnered by deploying systems which use the ‘emergent’ characteristics of networked media, particularly when allied to other techniques, within what Peter Morville describes as a multi-algorithmic combination of ontologies, taxonomies and what are called folksonomies. Equally, metadata can be captured through software i.e. speech-to-text conversion software can quickly and accurately generate keywords with spoken text. This could identify lyrical themes for example. Other software can be used to analyse and visualise the intrinsic structural components of music — see this recent analysis of visualising the improvisations in Miles Davis’ ‘All Blues’. Fascinating advances, though currently limited to niche interests. So metadata can ‘bubble up’ from a variety of techniques, but works best with the users themselves as active participants in the multi-algorithmic dance Morville describes above.]

Recommendation: Contextual information visible in the experience

So projects like Musicbrainz will help solve some of the metadata issues here, but further engagement with the physical interfaces of the device world — which Apple have done brilliantly, in a business sense — is going to be a fundamental part of future music experiences. Various software products from smaller players are trying to fold visual information and physicality back in to the music playback and discovery experience.

For example, Coverflow provides a browser layer for iTunes. In the notes from the Coverflow development site:

“Don’t know about you, but I find browsing a list of album names somewhat uninspiring, to say the least. One of the big appeals of a physical album is the beautiful packaging and aesthetic appeal, something that’s sorely missed with the digital equivalent. CoverFlow aims to bring that aesthetic appeal to your mp3 collection. It allows you to browse your albums complete with beautiful artwork pulled from any sources it can find …”

CoverFlow indicates a desire to engage with visual contextual information — to rediscover that in the discovery and playback experience. The application Retroplayer goes even further to replicate aspects of previous music experiences, even adding in the distortion, surface noise and jumps of the vinyl medium! Whilst this seems somewhat bizarre — actually building the negative aspects back in — it does indicate a real tension here; that some are trying to recapture an element of context, physicality, experience in playback.

Other visualisations are made possible by new media which could also be part of a richer music experience — for instance, this enlightening interactive map of what records have been sampled by what records [Java format]. Or these two superb Flash-based visualisations of John Coltrane’s ‘Giant Steps’, by Iain Houston and Michal Levy.

But what if such imaginative extensions and contextual information could be made visible, at least optionally, in an everyday music experience, just as record sleeves and liner notes were?

In terms of exposing metadata, I’ve previously suggested someone build a mini projector for the iPod, in order to enhance the listening experience with details of the track now playing. Whilst I mocked this up displaying only the basic iTunes metadata, the notion was to interleave metadata into the listening experience. This was based on the observation that the iPod screen can be metres away when listening at home, and there was no way of engaging with the music metadata as a result.

[Update: Since I gave this presentation, Apple has released new iMacs with a new interface called ‘Front Row’. These are computers designed to be part of the living room, a room in which music happens, with remote control and an interface which be seen from across the room, finally. Interestingly, the computer and media industries talk of the ’10 foot experience’ to capture this concept, but it’s been part of music experience since recorded phonography emerged. Could it be that the size of the 12″ vinyl sleeve unwittingly enabled a ’10 foot experience’ previously? Or its portability enabled a ‘3 foot’ or ‘1 foot’ experience?! Anyway … With Front Row, the cover art reappears in the music experience, alongside basic track details — again, the hegemonic artist-album-track power trio — but hardly to the extent that contextual information previously featured. It’s a step forward but still feels like a comparative diminution of the contextual experience.]

Recommendation: Develop tactile and embodied interaction

As noted previously, whilst there’s been an explosion of experience around music sharing and discovery, not only has that systems-led approach begun to encroach on the music itself, but much of the physical experience around music context is disappearing. Here again, history suggests that the music world should engage with technology to produce a truly rich device. If we look back to how great musical instruments handle simplicity and complexity within a user interface which is embodied, physical and scalable, we can learn a lot.

The user interfaces developed for musical instruments are often immediately intuitive and accessible, and then complex over time. The perceived affordances of a guitar or piano intrinsically convey how to play them — what parts make a noise — such that you can walk up to the instrument for the first time and create organised noise within seconds. Frankly, many records have been made shortly afterwards. An instrument like the electric guitar is flexible enough to describe an arc from Sid Vicious to Steve Reich. It takes seconds to figure out that hitting the strings in different ways makes different noises — but a lifetime to master the instrument. There is endless complexity beneath approachable simplicity.

Such instruments have often been built by the likes of Antonio Stradivari to Les Paul to Robert Moog i.e. instrument designers who were players too. They were of the world of music, rather than carpentry or electronics as such. Perhaps as a result, the interface choices are informed and honed by experience and insight as well as iterative development — again, a fruitful area for more research perhaps.

Tactile and embodied interaction in these new music experience products may be one of the most interesting avenues to pursue, creating bespoke interfaces for shuffle mode in which physical interaction based around muscle memory and gesture is imperative, due to the either the lack of screen or the device being pocketed, or for location-based music experiences enabled by ubiquitous computing. Timo Arnall has contributed some great thinking and sketches in this area.

(Ed. This balance of physical and digital would be a continuing obsession, in my own design work and writing about other’s, running from the design of light switches, music instruments, cellphones, planning notices, bike helmets, earpieces, signs, social printers, toasters, intercoms, aeroplanes, airport check-ins, wifi and libraries. But it started with music.)

Recommendation: Build-in future adaptation

Devices and experiences could be designed in ways which enable richer possible futures for listeners, rather than diminished ones. Product design, informed by the culture and history of the music world, could enable digital music devices with the intuitive user interfaces of a Fender Stratocaster or Steinway, with the eventual complexity and intrinsic interoperability to match. Otherwise, with the relentless driver of the bottom line, short cuts are taken in device design.

For example, unlike other iPods, the iPod Shuffle doesn’t have an internal system clock, which mean that it can’t be ‘synched’ with Last FM, with the result that the service cannot be made aware of the music you’ve played. This seemingly minor oversight leads to valuable contextual listening data being lost, meaning the device can’t learn from personal behaviour.

As ever, with technology and social networks, and informed perhaps by adaptive design theory, there is a powerful necessity to think long term; to not take such short cuts which may inadvertently delete possible outcomes; to enable the flexibility and endless modifications seen in previous generations of music devices. (Not just instruments, but playback devices too e.g. even apparently modernist perfection can be modified into Bootleg Objects.)

“That which is overdesigned, too highly specific, anticipates outcome; the anticipation of outcome guarantees, if not failure, the absence of grace.” [from William Gibson, All Tomorrow’s Parties]

Here more than ever, a need to build in adaptive possibilities means we can’t see this technology as separate to the music experience any more. Arguably, with perspective, it never has been — but too often education, policy and discussion around music has drifted away from engaging with the technology which generates products, systems and culture intrinsic to the music experience.

Again, our aspiration should be that hardware and software must not only retain the flexibility we’re used to — if anything it should increase it, not diminish it. So can we recreate the visuals, the flexibility, the tactility of experience, without being beholden to fetishising product, whilst still enabling the richness of the distributed experience?

The challenge remains to build something simple which can develop over time, something which grows as the user progresses. This would satisfy the product designer’s desire to create devices and experiences which are simple, intuitive and immediately compelling, but also enable a system to provide a slowly emerging architecture of knowledge, not just data. Upon this architecture, listeners can vault upwards, further enriching their listening.

Conclusion

“Digital formats were supposed to give music more room to stretch out. But music, in its frigid digital form, is unexpectedly brittle. Instead of stretching, it shatters.” [The Recording Angel, by Evan Eisenberg [p.237]

Despite all the focus on a business model seemingly under threat, there is more to music than the music industry. In fact, the focus on the sale of recorded phonography and its contemporary equivalents may have led to a collective oversight of some real opportunities and challenges in music experience in general — a far more important area.

Similarly, the sheer abundance of music apparently made available to consumers now — the total global aggregate of recorded music — has sometimes distracted us from real steps backwards in music discovery and experience. Mp3 players hold more songs in your pocket than was ever thought possible. But do people actually value all those songs? Are they really listening? Is a shared experience of music, in fact, shattering? The challenge seems to be to cram as much data as possible into one’s pocket, almost for the sake of it, like cramming students into a phone-box. Additionally, these devices are increasingly locked into business models which reduce the interoperability of music files in ways previous music devices never did.

So the volume of songs has increased, both in terms of music accessible to the average consumer and in terms of what their devices can hold — but currently it appears that important aspects of the music experience itself may be diminishing. This talk has concentrated on a few aspects of initial discoverability around music, and then ways of conveying contextual information such that listeners can discover more about music. Music needn’t shatter; we can enable it to stretch, flex and create ever-new ‘architectures of time’.

- Employ multidisciplinary design processes

- Rich metadata to provide rich context

- Contextual information visible in the experience

- Develop tactile and embodied interaction

- Build-in future adaptation

By testing the efficacy of the recommendations above we can perhaps fold true personality, texture, visual and contextual information back into the physical experience of music. We can synthesise the metadata with the data, the experience with the context, in ways which reinforce and enhance both. We can truly enrich “the social ritual of music”, as Eisenberg has it.

Please note that the recommendations I make are based on professional experience and informed guesswork, rather than detailed long-term ethnographic research into music discovery and listening behaviour across various contexts, discussion of music, acquisition and personal organisation of music — in short, all the facets of music experience. Personally, I’m yet to see such detailed, useful research, which could genuinely inform hardware and software product design.

However, some recent qualitative research by Human Capital commissioned by the BBC finds an increased sense of inquisitiveness and acquisitiveness for music, certainly amongst the UK population. I’d suggest that interest in music has only increased thanks to the extraordinary creativity in these new distributed discovery and listening music experiences. The iPod and the like has undoubtedly helped pull focus onto music. This is all good news.

But is that focus-pull going to be ultimately beneficial in enabling a richly articulated and variegated music world? And not just for those obsessives who will always find a way around a harshly controlled and stunted “Celestial Jukebox” imagined by Eisenberg in his final speculative chapter of the second edition of The Recording Angel.

Those who are currently hoarding personal collections of music and talking quietly to ever-decreasing circles of specialist music fans have a range of solutions thanks to the internet. But Eisenberg imagines the eventual personality of one such hoarder:

“When the Renaissance comes,’ Gramps says, patting his drive, “the species will thank people like me. We’ll be like the Irish monks who copied all those Latino manuscripts onto potato skins and saved civilization.”

This argument hasn’t been about ‘Irish monks’, audiophiles or equivalent — the various chapters on obsessives in Eisenberg make clear the difference between that and a sense of everyday music experience. The latter should be the focus of our work, in order to create the variegated architecture of knowledge I described earlier in which people can find their own place in this richest of cultural fields. We must not lose a deep, personal, visceral, physical and intellectual connection with music and the context around music, for everyday people as well as fans, academics and musicians.

Thurston Moore, in Mix Tape, notes that:

“Trying to control sharing through music is like trying to control an affair of the heart — nothing will stop it.”

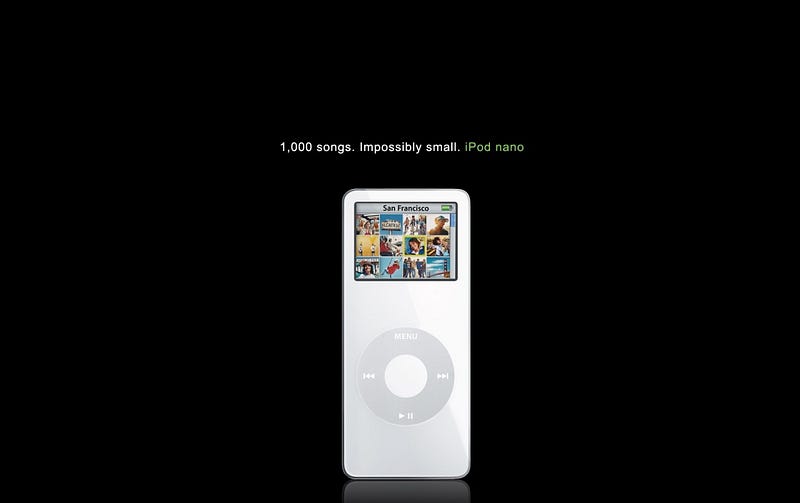

He may be right. But if we, those responsible for crafting the frameworks for music experiences, are negligent, irresponsible, careless or misdirected we might inadvertently end up stunting music experience altogether — and reducing something that was truly “insanely great” to merely “impossibly small” indeed.

Addendum