Reading from Waxwings, writing about places

Ed. This piece was originally published at cityofsound.com on 28th August 2003.

I went to hear Jonathan Raban read from his new novel Waxwings, which I mentioned earlier, at the London Review Bookshop this evening. It was good. Here’s some notes.

Raban preceded the reading by slyly noting “how tiresome it is to be read to in bookstores”. Well, I must be lucky — I’ve only ever been to two: this and William Gibson in Manchester Waterstones in about ’95. Both were great.

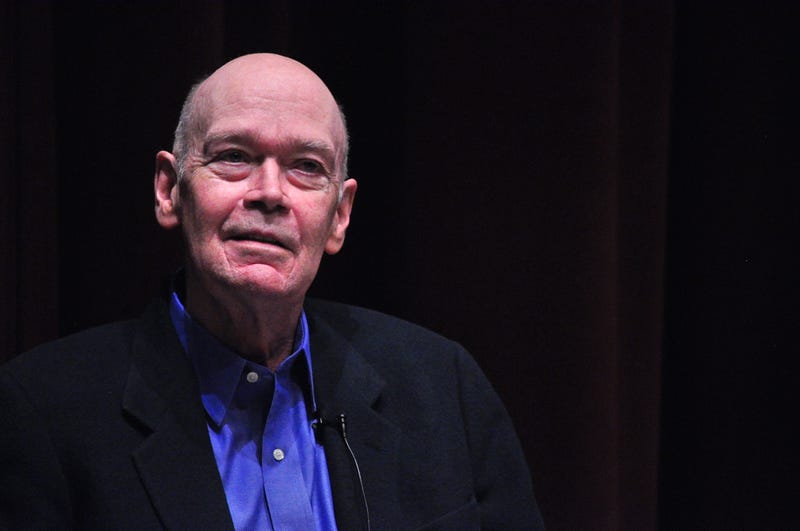

Raban is physically smaller than I imagined, wearing his seemingly permanently affixed baseball cap. His teeth betray his status as an Englishman defiant in America — like mine, two craggy mountain ranges. He possesses a rich, warm, sonorous voice, betraying further evidence of his Englishness; a confident, erudite speaker, and yet punctuated with ums, ahs, and a halting hesitancy.

Raban described Waxwings as “a historical novel” set in a “bygone age” of 1999, 2000. An age not of innocence, but about the end of an era nonetheless. Set in an “imaginary city”, which is basically Seattle, in the midst of the dotcom bubble, it’s based around the intertwining stories of 4 immigrants. Read more at Amazon or The Guardian for the synopsis. I almost fell asleep during the actual reading, not due to the text which sounded typically compelling, or Raban’s sardonic but attractive reading style, but as predicted it is tiresome to be read to.

But the book sounded great. However, the Q&A woke me right up. It was more engaging, and perhaps more interesting.

First up, Raban discussed his penchant for writing fictionalised non-fiction, and then fiction with real-life characters and events, blurring these boundaries. He noted you can easily tell the difference as non-fiction always has a subtitle, whereas novels take the form ‘title’ then the subtitle, ‘a novel’.

He described his writing as “prose narratives”. That the word fiction itself doesn’t come from some imagined Latin verb meaning ‘I made things up’, but it comes from the actual Latin verb fictio which means ‘give shape to’. So he saw his role as plotting, shaping, devising and identifying patterns, the knitting together of existence.

This doesn’t really matter if its actual or “un-actual” people, places, or events. Waxwings, although fiction, contains lots of real events, real people, and real streets. So it’s more of a continuum within his writing rather than absolute opposites, a theme which echoed his breakthough book, 1974’s brilliant Soft City, one of the definitive texts on cities. And it’s a particular continuum within his writing; from Badland to Passage to Juneau to Waxwings. From non-fiction to fiction, but not from black to white. Raban described the feeling as “a slippage”, rather than “now I am writing a novel”. [Ed. Those unfamiliar with but interested in Raban should probably start with Badland, Passage to Juneau, Hunting Mr. Heartbreak, and Soft City. Just superb books.]

Raban noted that the novel was called ‘the novel’ in the 19th century because it was just that: novel. It was an entirely new, mixed form of documentary journalism with “made up stuff”; “a low form”, as compared to writing proper books about history etc. And it’s only since Henry James that the novel has assumed some preeminent status as a “rarefied form”. These days, the thing that Raban is often filed under, in bookshops who have problems with faceted classification schemes, is travel writing — as that’s the only place to put books about place, it would seem; ironically, today’s low form, despite Raban, Chatwin, and Theroux.

When asked whether Seattle was a fifth character in the book, Raban said that Seattle was intended to be the representative American city of the late 20thC — the cutting edge city in the US from the mid-’90s on, central to the US, the place to be.

As such, it formed an important role in terms of setting up this book as recording the end of an era. Having been in England and Scotland (Edinburgh festival) for the last week or so, he’d been quite surprised at how differently people here view the world right now, as compared to the US. This had manifested itself in British press reviews, where people hadn’t necessarily ‘got’ quite as clearly the fin-de-siecle, millennialist doom coming in throughout the book. In the US, Raban felt that most Americans sense that the world changed conclusively for the worse during this time, in a quite radical, harsh, and almost cataclysmic way — we had the NASDAQ crash; the election of Bush; 9/11, but more dangerously, the US-led response to 9/11; the Patriot Act; neighbourhood spies; Paul Wolfowitz in the White House etc. Leaving aside the politics, these are quite different times. The book contains all the clues — the tea leaves in the tea cup — in order for readers now to perceive that these changes were just around the corner, beginning to seep into the reality of the characters in the book. Raban found it fascinating (and it is) that British people he’d spoken to hadn’t really got this, as they hadn’t really felt the shift that the US had; that their everyday life hadn’t really changed that radically.

Consquently, they just didn’t pick up on the fact that it’s a historical novel about the end of an era, the last days of innocence before a new world order emerged. Raban suggested that analogues might be novels set in an English country home in July 1939, or amidst some Anglo Saxons, somehow unaware of the Norman, in 1065!

When asked, inevitably, if the book was semi-autobiographical (Waxwings is about an English literary type, divorced with a kid, living in Seattle; Raban is a writer who generally weaves himself into his non-fiction, divorced, with a kid, living in Seattle), he denied it. He said he writes about “people’s place in places and their displacement from it”, and said that one of the ‘upsides’ of being divorced is that it provides “useful” material for writing, and in a sense, everything is “grist” for a writer.

More interestingly, Raban returned to one of my favourite conceits of his: the novel-sized city. The idea comes from his book Hunting Mr. Heartbreak, in a section on Raban arriving in Seattle for the first time. Noting how people sometimes poke fun at the ridiculous coincidences Dickens relied on when writing about mid-19thC London i.e. key protagonists accidentally bumping into other key protagonists in the busy streets, thereby sprouting unlikely plotlines, Raban notes that the population of London at that time was 1.7m people. Seattle now is 1.7m people. Raban’s not totally serious point is that there may be an optimum size of city to generate the coincidences required to write a certain kind of novel, that Seattle feels “novel-sized”.

This link between demography and novels and coincidence is very interesting, I think — I wonder if there are also parallels to social software. Matt Jones (via a typically lovely diagram) and JC Herz (RE multi-user games), have talked about the different sizes of social groups online, and the characteristics and patterns enabled therein. Does the city work in a similar way, in terms of enabling connections and nodes at different scale points? What can we learn from that? There’s more in Emergence on this, and the original sources such as Jane Jacobs et al.

Anyway, Raban went on to observe that Dickens, with his particular genius, sure, could capture the entire city in one of his novels. You read Our Mutual Friend, you get a sense of London in its entirety. It could be argued Raban, er, argued, that there has been no great mid- to late-20thC novel about London which captures the whole city. What you have is books, like Martin Amis’ London Fields, that are brilliant on a focused portion of London. London is now too big for the form of the novel.

On his next books, again he described how his “novels were shaped by geography”. Next up is something about Seattle, and an island off the coast. Then he has a hankering to write about Seattle and its bizarre relationship with the surrounding country — Seattle, as probably the most liberal city in the US, and yet just over the Snowqualmie Pass, the weather changes in many ways and you’re in a land of the most extreme right-wing Christian fundamentalists, where every church has a broadcast tower, from which they issue diatribes against the city over yonder as if Seattle was actually Sodom and Gomorrah combined.

Much of the above would seem to echo the sentiments of the Vulliamy article I referred to previously, but when asked why he still lived in the US, Raban replied that he had a daughter there but that even if he was free to move he probably wouldn’t. He still finds the America the “most interesting, albeit scarifying”, place to be. And compared to London, Seattle is completely preferable: small enough to be novel-sized(!), but actually at the centre of things in a way London isn’t, that there is a ‘there’ there, and all roads lead down to the sea…

Very enjoyable, very interesting.

Ed. This piece was originally published at cityofsound.com on 28th August 2003.

Leave a comment