Designing from matter to meta

Ed. The following is adapted from a section of my book Dark Matter & Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary. Read more about the book here.

It’s been quite a month for dark matter. While the latest twist in the Hunt for Higgs Boson thoroughly owned the much-coveted theoretical physics research news agenda, other theoretical physics research news had also emerged, with the bad timing of a wedding on cup final day, revealing a major breakthrough in the hunt for dark matter.

Scientists had used “gravitational lensing” — a favourite new barely understood concept I’ll be using a lot — to detect some evidence of the essentially imperceptible dark matter; that which Must Be There For Everything Else To Be There. As explained here, and thanks to Gill Ereaut for the link:

Something invisible with mass, like dark matter, is bending the light from the cluster of galaxies. So although we can’t see the dark matter, we can see it affecting the light’s path and take a pretty good guess it is there.

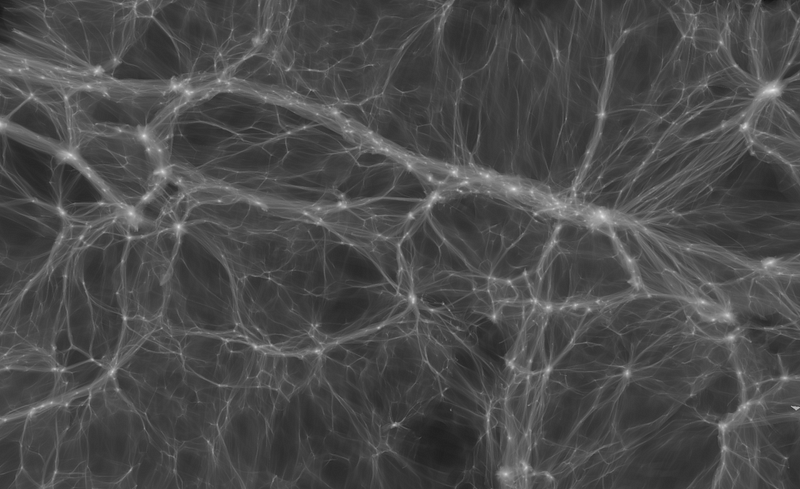

ArsTechnica suggests these experiments “support to the theory that the Universe is built on a web of dark matter.”

Yet few people will have noted this, given the kerfuffle over Higgs and the abstract nature of the research. Ironically, even news about dark matter is difficult to perceive.

In this case, it’s this very imperceptibility combined with its fundamental influence which attracts me to it as a concept. For the last year or so, I’ve been using the concept of dark matter as a metaphor in strategic design to describe the often imperceptible yet fundamental facets — the organisational cultures, the regulatory or policy environments, the business models, the ideologies — that surround, enable and shape the more tangible product, service, object, building, policy, institutions etc.

I drew this from the great Dutch architectural historian Wouter Vanstiphout’s inspired, off-the-cuff comment in conversation with Rory Hyde, where he suggested that this is the stuff you have to engage with:

“If you really want to change the city, or want a real struggle, a real fight, then it would require re-engaging with things like public planning for example, or re-engaging with government, or re-engaging with a large-scale institutionalised developers. I think that’s where the real struggles lie, that we re-engage with these structures and these institutions, this horribly complex ‘dark matter.’ That’s where it becomes really interesting.” (Vanstiphout, interview with Rory Hyde, 2010; now also available in Rory’s new book Future Practice)

Wouter’s notion of dark matter suggests organisations, culture, and the structural relationships that bind them together as a form of material, almost. Usefully, it gives a name to something otherwise amorphous, nebulous yet fundamental.

Dark matter is a choice phrase. The concept is drawn from theoretical physics, wherein dark matter is believed to constitute approximately 83% of the matter in the universe, yet is virtually imperceptible. It neither emits nor scatters light, or other electromagnetic radiation. It is believed to be fundamentally important in the cosmos — we simply cannot be without it — and yet there is essentially no direct evidence of its existence, and little understanding of its nature.

Physicists like Fritz Zwicky had been searching for it since the 1930s at least; he dubbed it “the missing mass”. (Things worth noting: Zwicky also came up with the concept of “tired light”.)

The only way that dark matter can be perceived is by implication, through its effect on other things. Essentially, it is perceived by proxy, via the gravitational effects it has on more easily detectable matter.

But despite the provenance of Wouter and Rory’s conversation, this seemed to me not only apply to the city, but also to institutions and governments, the public sector generally but also companies and firms, politics and commerce.

With a product, service or artefact, the user is rarely aware of the organisational context that produced it, yet the outcome is directly affected by it. Dark matter is the substrate that produces. A particular BMW car, say, is an outcome of the company’s corporate culture, the legislative frameworks it works within, business models it creates, the patent portfolio that protects, the wider cultural habits it senses and shapes, the trade relationships, logistics and supply networks that resource it, the particular design philosophies that underpin its performance and possibilities, the path dependencies in the history of northern Europe, the culture of the Mittelstand and so on.

Equally, the iPhone, say, is successful not simply due to Jonathan Ive’s team’s designs but also Apple’s lawyers, their intellectual property holdings, their creative interpretation of the legislative environment, their grip on manufacturing and logistics networks framed in contracts and agreements (including moves that prevent competitors using the same infrastructure or raw materials), their deals with telecoms companies, with record labels, with movie studios, their organisational culture, their ‘parallel production’ model of interdisciplinary work, and so on. This is all dark matter. You can’t perceive any of it, holding the iPhone in your hand, but it is all this, and more, that makes the thing a successful product and service.

A better, if less tangible (obviously) example would be Amazon . I’d argue most of its success has been through manipulating dark matter. You can’t perceive their extraordinary logistics operation, their data centres, their discovery algorithms, the way they artfully manipulate the structures of taxation with almost admirable skill. The matter, or equivalent, is perceptible in a) the thin veneer of their website, and b) cardboard packages arriving in the post. But getting from a) to b) so successfully is all down to innovation in dark matter.

So the answer to unlocking a new experience, product or service is sometimes buried deep within organisational culture, regulatory or policy environment.

This is all dark matter; the car, or phone, or parcel, is the matter it produces.

Similarly, the city we experience is, to some extent, a product of a city council’s culture and behaviour, legislation and operational modes, its previous history and future strategy, and so on. The ability for a community to make their own decisions is supported or inhibited by this wider framework of dark matter, based on the culture of the municipality they happen to be situated within as well as the characteristics of their local cultures.

This “missing mass” of dark matter is the key to unlocking a better solution, a solution that sticks at the initial contact point, and then ripples out to produce systemic change. It is what enables these things to become normative. It is the material that absorbs or rejects wider change.

It is organisational culture, policy environments, market mechanisms, legislation, finance models and other incentives, governance structures, tradition and habits, local culture and national identity, the habitats, situations and events that decisions are produced within. This may well be the core mass of the architecture of society, and if we want to shift the way society functions systemically, a facility with dark matter must be part of our toolkit.

Note that contextualising Ive’s team above does not imply a diminishing of their importance; in fact, their particular success will be down to the way they understand and manipulate dark matter as well as physical matter (though all you really hear about is their facility with the latter.) In fact, this should imply an expansion of design’s ambit, its range, its toolkit. It should enable design to be genuinely useful.

Without addressing dark matter, and without attempting to reshape it, we are simply producing interventions or installations or popups that attempt to skirt around the system.

This is a valid tactic, but not much of a strategy.

A strategy would focus on delivering the intervention whilst also enabling the positive energy it creates to be easily drawn into the system, to shape it over time. (This is often why there’s such a gulf — of time, or in realisation — between student projects or the output of research labs and those same ideas or technologies hitting the street. It’s not the idea or the technology that matters, but how you combine that with its dark matter.)

This is a balancing act, as too much time spent immersed in dark matter can lead to nothing being produced, and change is best enabled through prototyping, through making, through demonstrating — through, yes, working with matter. Traditional consultancy tends to only deal with ‘dark matter’ exclusively, rather then synthetically produce an alternative or tangible iteration, and so its effects are hugely limited as a result. So it’s the balance of matter and dark matter that, well, matters.

For instance, our Brickstarter project is trying to produce something tangible — a physical/digital system, based around real-life case studies — but the Brickstarter project also wants to engage with the dark matter around it, taking advantages of Sitra’s unique position as a public body, such that our prototyped cultures of decision-making might be positively absorbed into wider systems of governance, and so ripple out across Finnish society and beyond. Again, a delicate balancing act. One of our Low2No project’s major innovations was in helping change the building codes in Helsinki — classic dark matter, that — to enable large timber buildings. That outcome is systemic, beyond a simple plot of land in Helsinki. Now there are several large timber buildings going up in southern Finland. In a city, the building regulations are the code that writes the city, the dark matter that enables, or inhibits, particularly patterns of development. Architecture could spend a little more time focusing on redesigning building codes, and not simply buildings, in order to have a greater effect on the city.

The idea of dark matter might be relevant beyond Sitra, and beyond Brickstarter. At this point, I’m taking Wouter’s comment — which he later told me was invented on the spot (quite briliantly I must say) — and running a mile with it.

But sometimes you have to put a name on something to get a handle on it.

More on how the concept of dark matter helps design — and vice versa — in the book Dark Matter & Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary, out now on Strelka Press.

Ed. The following is adapted from a section of my short book for Strelka Press, Dark Matter & Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary, available via print-on-demand, e-book and some bookshops. Read more about the book here. This piece was originally published at cityofsound.com on August 7, 2012.

Leave a comment