A music streaming service hints at where new and old media might be going in the near future

Ed. This piece was first published at cityofsound.com on 27 February 2002. Echo Networks didn’t last more than a year beyond this post being published, yet its basic patterns, extending Amazon’s ‘collaborative filtering over a large catalogue’ model into streaming media, influenced almost everything that followed, in terms of music and media user experience, and ultimately the likes of Netflix, Apple, and Spotify. Many of those patterns were seen with Echo first. It was a Flash-based player controlling embedded Real Audio streams which continually streamed tracks based on your feedback. It was as simple as that, in a way, but this was almost radical in 2002. This report can be read as a companion piece to New Musical Experiences.

I’ve been using Echo.com for almost a week now and I’m addicted. Not just to using it, but addicted to trying to think through the implications of it.

First things first, the user experience is fabulous. Very simple and neat, it’s been beautifully thought-through. The whole device is so unassuming that the implications of Echo are not immediately obvious.

Its ‘radio-ness’ is evident in several ways:

- It’s not about downloading. Music is not about storage but experience and performance.

- It suggests things to you. It’s a stream of suggestions. The delightful surprise element of radio is there to the extent that I’ve just skipped through tracks without listening to them just to see what Echo suggests.

But it’s radio-not-radio. The ability to skip tracks is akin to TiVo’s ‘pause live TV’ feature. In that, as Negroponte would say, we then have asynchronicity. The radio starts when you launch the window; it stops when you close it; you can skip any track you don’t fancy.

More than that, it’s radio that learns. It learns quickly, too. In fact, it almost becomes addictive to actually ‘play’ with the sound down, skipping through the tracks, just to rate even further (but then I’m the kind of person who has voluntarily spent time rating Amazon recommendations. I actually enjoy filling out surveys). Watching it learn is fascinating. My colleague Chris Jones described it as a ‘musical tamogotchi’. Hearing it play your favourite record unprompted is almost akin to witnessing a fawn’s faltering first steps. Almost.

The instant messaging and community aspects are very smart too. You quickly become embedded within behavioural cycles of nurturing your radio station; visiting others’ stations; engaging in late-night chat about music with fellow listeners; watching what others are listening to and rating those tracks; ‘infecting’ others radio stations with your tastes; thinking of artists to check against its database and requesting that their music joins your potential mix. Its collaborative filtering engine is open to a rich seam of influence in the way Amazon’s is—perhaps even more so. It’s so many-to-many, plus their suggestions go beyond collab-filtering, I’m sure of it. There seems to be additional biographical and discography-based connections. It feels richer than simply taste-based filtering, as supremely powerful as that is.

In the meantime, Echo is quietly building the mother of all music databases, tracking its users’ musical tastes in mindblowing detail. These musical connections have hitherto been impossible to manage but suddenly we can really experience the power in hooking up user’s tastes to an emergent system. Hearing a radio station learn and live is a far more enjoyable than window-shopping at Amazon (a site browsed by some information architects for fun).

I think it’s worth quoting this lengthy passage from Steven Johnson’s recent Emergence as, although it refers to TiVo, it outlines exactly what these collab filtering/community-based devices mean for traditional media organisation and consumption.

“But TiVo and Replay — and their descendents — will also fall under the sway of self-organization. In five years, not only will every television set come with a digital hard drive — all those devices will also be connected via the Web to elaborate, Slashdot-style filtered communities. Every program broadcast on any channel will be rated by hundreds of thousands of users, and the TiVo device will look for interesting overlap between your ratings and those of the larger community of television watchers worldwide. You’ll be able to build a personalized network without even consulting the channel guide. And this network won’t necessarily follow the ultrapersonalization model of the ‘Daily Me’. Using self-organising filters like the ones already on display at Amazon or Epinions, clusters of like-minded TV watchers will appear online. You might find yourself joining several different clusters, sorted by different categories: retirement-home senior citizens; West Village residents; GenXers; lacrosse fanatics. Visit a channel guide for each cluster, and you’ll find a full lineup of programming, stitched together out of all the offerings available across the spectrum. Despite the prevailing conventional wisdom, the death of the network programmer does not augur the death of communal media experiences. If anything, our media communities will grow stronger because they will have been built from below … To be sure, our media communities will grow smaller than they were in the days of All in the Family and Mary Tyler Moore — but they’ll be real communities, and not artificial ones conjured up by the network programmers. [p212–213]

[…]

In the end, the most significant role for the Web in all of this will not involve its capacity to stream high-quality video images or booming surround sound; indeed, it’s quite possible that the actual content of the convergence revolution will arrrive via some other transmission platform. Instead, the Web will contribute the metadata that enables these clusters to self-organize. It will be the central warehouse and marketplace for all our patterns of mediated behaviour, and instead of those patterns being restricted to the invisible gaze of Madison Avenue and TRW, consumers will be able to tap into that pool themselves to create communal maps of all the entertainment and data available online. You might actually have the bits for ‘The Big Sleep’ sent to you via some other conduit, but you’ll decide to watch it because the “Raymond Chandler fans” cluster recommended the film to you, based on your past ratings, and the ratings of millions of like-minded fans. The cluster will build a theory of your mind, and that theory will be a group project, assembled via the Web out of an unthinkable number of isolated decisions. Each theory and each cluster will be more specialized than anything we’ve ever experienced in the top-down world of mass media. These mind-reading skills will emerge because for the first time our patterns of behaviour will be exposed — like the sidewalks we began with — to the shared public space of the Web itself.” [p220–221]

I’m not sure about Johnson’s assertion that all media brands (like HBO) will diminish in the eyes of the consumer. It may be that, with a little reorientation, the media brands provide the information layer, or filter agents, or other tools/devices that enable this coalescing to occur. Some broadcast organisations already have a useful track record of such technical/IT innovation.

But just as TiVo places the traditional model of broadcast TV in doubt, so Echo presents a real challenge to radio. Will radio pick up the gauntlet, or quietly fade away?

There are huge opportunities for traditional broadcasters beyond simply becoming programme producers. I aim to pick this thread up properly later but it strikes me that, whilst the web-based rating systems Johnson outlines could provide online communities with self-regulating special interest groups, there are still some media brands which firmly engender notions of trust and quality — which is still important online — and could build on their reputation for technical innovation. It could be a question of reorienting media to provide the layer this interaction occurs within — to truly be a medium.

A few potential developments that would make Echo rock even more:

- Integrate a speech radio channel, comprised of the best bits of speech content (we could unbundle speech from its network, in the way we’re unbundling music from the physical package of an album); I’d love to hear a bit of I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue and WNYC’s Studio360 juxtaposed with Alistair Cooke’s Letter From America and a bit of Robert Elms (news can come from other sources).

- Hook it up to my iTunes so that Echo knows what’s on my hard-drive, mp3wise, and slips in a few of those too (it could share these worldwide too, but then we’re into a slightly different business model, and probably a world of pain at this point). I could also request to immediately hear a track ‘I own’ that way too, but then again, that’s a subtle shift in offering. In this way, new music could be filtered in more. If Echo has a drawback, its 60,000+ songs are a bit ‘back catalogue’; currently DJs are more connected to new sounds. However, if something remotely p2p could be engineered in (or if the encoding request queue was quicker/interactive), new sounds could abound in a way the one-to-many DJ model can only dream of.

- Of course, it’d be great to hear it on an iPod crossed with DAB (the latter would be perfect for that, with its high-bandwidth capability — but I’m yet to see a DAB box designed with ratings buttons on the front — why?).

- Some kind of visual representation of your emerging music map would be fascinating, and potentially super-powerful. Whilst text links do an incredible job, I’d love to be able to tweak genres and subtly inflect artist relationships by pulling a web of connections around. A job for Wattenburg? There’s still not much out there on music maps. Yet.

People will say “What about serendipity?” But it’s all built-in. Ultimately, that’s just a slider control. The ‘listen to old faves or new music?’ control at Echo is already there. People will say what about personality radio? That’s just listeners/users coalescing around certain types of content, in this case personality types. That can still happen, it’ll just be John Peel fans rather than Radio One fans — the network has always been an approximation (I doubt there are that many Sara Cox listeners who frequent Peel fansites).

The only thing Echo hasn’t made clear yet is its business model.

Have a good look at, and listen to, Echo. It embodies so much of where both new and old media might be going in the near future.

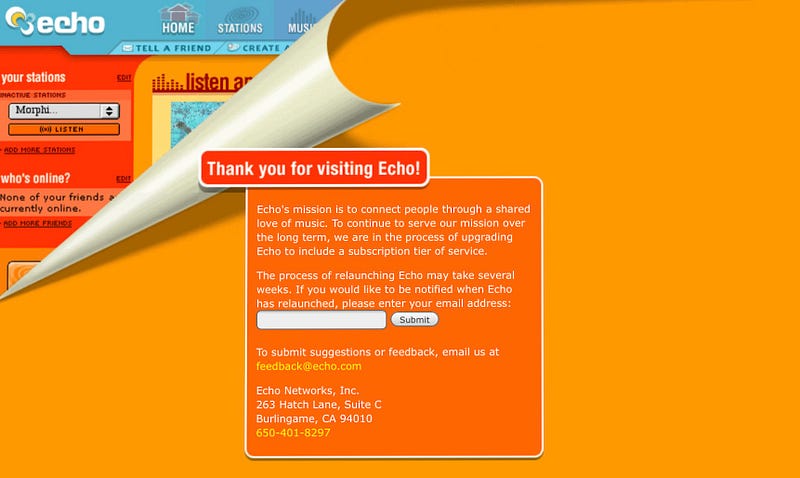

Ed. This piece was first published at cityofsound.com on 27 February 2002. As noted at the top, Echo was shuttered within a year. The

See also: New Musical Experiences

Leave a comment